Last week, I wrote about the two fluencies that professional composers must have: technique and process.

Professional composers generally all achieve a baseline of technical fluency. Many, especially those in media music, also develop a reliable process fluency.

Without both fluencies, you can’t be like Michael Giacchino, for instance, and take on a project like Rogue One last minute — with only 4½ weeks to score and record it — and then complete it while still working steady hours of 9 AM-6 PM.

Sounds like an valuable skill, right?

Surprisingly, many professional composers — particularly those writing concert music — never develop such a reliable process:

- They put off getting started, then struggle to get and stay inspired.

- They foreground their insecurities and rarely accept anything as “good enough.”

- They consequently blow past deadlines like weeds along a freeway median.

I will refrain from naming professional composers who’ve done this with commissions from world-class orchestras. We’ve all heard the gossip — and, at some time or another, we’ve all been there.

But we can refuse to stay there.

A Professional Creative Process

So what does a professional-level compositional process look like?

It has six key elements, or “workspaces”:

- Consulting

- Connecting

- Sketching

- Assembling

- Revising

- Shipping

These workspaces are NOT a series of steps, nor typically are they discrete, physical locations. Rather, they reflect different ways of thinking about, relating to, or interacting with our music and our collaborators.

Let’s examine each of these elements in turn . . .

Consulting

This workspace is where you determine your patrons’, employers’, and collaborators’ needs. Often the starting and ending point of the creative process, it shows up in the middle not infrequently, too.

This workspace is where you determine your patrons’, employers’, and collaborators’ needs. Often the starting and ending point of the creative process, it shows up in the middle not infrequently, too.

This is where you ask questions to hear and internalize your collaborators’ needs and desires, where you brainstorm together to develop ideas, and where you go to enrich your own ideas with other perspectives.

You can visualize this workspace as a big conference room table (with donuts or other snacks!), a set of comfortable couches, or even the booth at your favorite restaurant or bar — anywhere you can picture yourself sitting, talking, and hanging with your collaborators.

Connecting

“Connecting” is where you cultivate inspiration actively rather than waiting for it to “just happen.” This workspace is what many composers call “pre-composition” (though, like all six workspaces, it is used throughout the creative process).

“Connecting” is where you cultivate inspiration actively rather than waiting for it to “just happen.” This workspace is what many composers call “pre-composition” (though, like all six workspaces, it is used throughout the creative process).

My favorite way to visualize this space is as a big “conspiracy wall.”

Your job here is to make meaning — to identify why you care about what you’re writing:

- How does this current project relate to your past ones?

- What specifically influences this current project?

- A treasured memory? A recent experience you just had?

- A TV show you were just watching?

- A line from a book you just read?

- Certain passages or whole pieces of music?

- What kinds of connections might others make to what you are creating?

The ideas you generate here all count. They’re all valuable even if they never show up in the final piece.

The goal here is to make it easy and inevitable for you to write music, because you have developed something to say.

Sketching

Sketching is the sandbox of the creative process. It’s play time. It’s magic markers and play dough and make believe.

Sketching is the sandbox of the creative process. It’s play time. It’s magic markers and play dough and make believe.

This workspace is where the rubber hits the road: namely, where you convert your inspiration into pitches and rhythms (notated or recorded).

The goal of sketching depends on where you are in writing your piece:

- “Assembling” requires ideas to arrange. Sketching creates those ideas.

- “Revising” needs alternatives to composed phrases. Sketching creates those alternatives.

By definition, every idea here is half-baked and incomplete because they are all at the service of assembling and revising. This recognition can free you from the tyranny of perfectionism.

Assembling

Assembling is the workbench of the creative process. It reflects the literal definition of the word compose: namely, to put together. It’s where you organize and assemble your sketches into complete phrases, phrase groups, and sections.

Assembling is the workbench of the creative process. It reflects the literal definition of the word compose: namely, to put together. It’s where you organize and assemble your sketches into complete phrases, phrase groups, and sections.

Composing complete phrases is essential to working happily and effectively in the “Assembling” workspace. Because phrases are the shortest unit of a complete musical thought, if you fixate on shorter or longer timescales, you will struggle to get a firm grasp on just what your musical thoughts are.

This focus on phrases and sections also helps you escape the “left to right” mindset. Because the Assembling workspace results in complete musical thoughts, you can shuffle around and develop these thoughts without having to peg them to a certain place on the timeline.

Now, what counts as a complete phrase varies by composer and project. Sometimes, and for some people, this includes the full orchestration. For others, the arrangement and production are tasks part of the “Revising” workspace.

What matters in this workspace is that you include all the details necessary to capture your complete musical thought, phrase by phrase.

Revising

Revising is like staining, decorating, and sealing a piece of woodworking. This is where you deepen connections between phrases, remove excess details, and polish the remaining ones.

Revising is like staining, decorating, and sealing a piece of woodworking. This is where you deepen connections between phrases, remove excess details, and polish the remaining ones.

This workspace is often where craft takes over from creativity.

This workspace is often analytical. Its goal isn’t to render a judgment on artistic worthiness but to exercise discernment. Here you ask questions like:

- How well does this passage capture my inspiration?

- Is it clear that I want this passage to be the focal point and not that one?

- What technical tools can I use to enhance these relationships?

Somewhat paradoxically, by focusing the mind on specific details, this revising workspace liberates the unconscious (or the muse, whatever you want to call it) to speak more clearly by harnessing a tool called mental simulation.

Shipping

Shipping is the mundane bit: the concession that “my musicians want sheet music to play from” or “the sound editor needs stems he can create the show’s final mix with.”

Shipping is the mundane bit: the concession that “my musicians want sheet music to play from” or “the sound editor needs stems he can create the show’s final mix with.”

This grunt work includes work like tidying the notation, proofreading the score, making parts, or mixing and mastering your track.

In early stages of a professional career, composers often have to do these things themselves, but as they become more established, shrewd (and otherwise busy) composers outsource these tasks to other people.

Between managing outsourced tasks and confirming deliverables, work in this space often happens in tandem with Consulting.

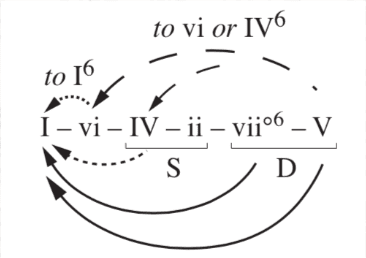

These Workspaces Are NOT a Timeline

If you are a professional composer or have been working to become one, all these workspaces will sound familiar to you.

However, one of the biggest mistakes people make when conceptualizing the creative process is imagining it as a linear process through time.

The professional creative process I describe is best understood spatially.

Your creative process is NOT a specific ordering of these workstations. It is not a series of “stages” or a timeline. Rather, it is the ever-changing paths you trace between them.

Thinking in these terms helps you avoid getting fazed whenever the path of writing “this piece” looks different than the way you wrote “the last one.”

Indeed, that path inevitably varies from project to project:

- Sometimes it looks like, “Sketch → Assemble → Connect → Consult → Revise → Connect → Revise → Ship.”

- Or it can look like, “Consult → Connect → Sketch → Assemble → Connect → Sketch → Revise → Ship.”

- Or any of an endless number of permutations.

For some projects, you might even hardly use some of the workstations.

Likewise, the time you spend in each workstation is typically not measured in days or weeks. Usually, in any single workspace composers spend at most a few hours, but often as little as a few minutes.

This frequent turnover happens because these workspaces describe the nature of what you’re doing, not an overall roadmap.

Again, thinking in terms of workspaces can lessen your anxiety, because the answer to “Where should I be right now?” isn’t a pre-determined checklist.

Instead, it is the encouraging assurance, “You only ‘need’ to be in whatever workstation would best help you advance the project and maintain your energy and enthusiasm.”

Why You Need a Professional-Level Creative Process

The primary challenges that technically proficient composers face are process issues.

These process issues usually do not signal technical deficiencies. They are also not artistic indictments or moral failings.

And, most of the time, they are not cause for existential meltdowns. (As a professional, you will have those occasionally because you’re human, NOT regularly because you are a composer.)

A professional creative process collects the rain of your inspiration into a river of steady output. Like good floodplain management, it mitigates creative emergencies:

- It gives you tried and tried practices and frameworks so you can navigate everyday creative questions with hardly a second thought.

- It prevents major creative issues from happening frequently.

- When major issues do happen, it ensures that you can get through them with minimal anxiety.

The creative process model I describe above does all this. This is why, when describing the Four Elements of Compositional Magic, I call it Flow and associate it with water.

In future posts, I will show how this Flow magic (water) works together with World Building (earth), Sleight of Hand (air), and Inspiration (fire) to help you reliably create musical magic.

This workspace is where you determine your patrons’, employers’, and collaborators’ needs. Often the starting and ending point of the creative process, it shows up in the middle not infrequently, too.

This workspace is where you determine your patrons’, employers’, and collaborators’ needs. Often the starting and ending point of the creative process, it shows up in the middle not infrequently, too. “Connecting” is where you cultivate inspiration actively rather than waiting for it to “just happen.”

“Connecting” is where you cultivate inspiration actively rather than waiting for it to “just happen.” Sketching is the sandbox of the creative process. It’s play time. It’s magic markers and play dough and make believe.

Sketching is the sandbox of the creative process. It’s play time. It’s magic markers and play dough and make believe. Assembling is the workbench of the creative process. It reflects the literal definition of the word compose: namely, to put together. It’s where you organize and assemble your sketches into complete phrases, phrase groups, and sections.

Assembling is the workbench of the creative process. It reflects the literal definition of the word compose: namely, to put together. It’s where you organize and assemble your sketches into complete phrases, phrase groups, and sections. Revising is like staining, decorating, and sealing a piece of woodworking. This is where you deepen connections between phrases, remove excess details, and polish the remaining ones.

Revising is like staining, decorating, and sealing a piece of woodworking. This is where you deepen connections between phrases, remove excess details, and polish the remaining ones. Shipping is the mundane bit: the concession that “my musicians want sheet music to play from” or “the sound editor needs stems he can create the show’s final mix with.”

Shipping is the mundane bit: the concession that “my musicians want sheet music to play from” or “the sound editor needs stems he can create the show’s final mix with.”

And then there’s the big elephant in the room: How does music take listeners on a journey that gives them goosebumps or takes their breath away? The common curriculum avoids the question entirely, even though

And then there’s the big elephant in the room: How does music take listeners on a journey that gives them goosebumps or takes their breath away? The common curriculum avoids the question entirely, even though