If you’re like me, your number one love is writing music—but your number one skill is avoiding writing music. Every day, we find some “good” reason to avoid writing:

- I don’t have enough time

- I don’t have the emotional energy for it

- I don’t feel inspired

- I don’t know how to write what comes next

- I don’t know what comes next

- I don’t have the performers or the commission

These excuses reveal what Steven Pressfield calls your “Resistance”—the shadow part of yourself that keeps you from working.

Why would your Resistance do this to you? Why would it keep you away from the thing you love? Because it’s trying to keep you safe.

Safe from what? Ironically, your own impossible expectations.

The Weight of Impossible Expectations

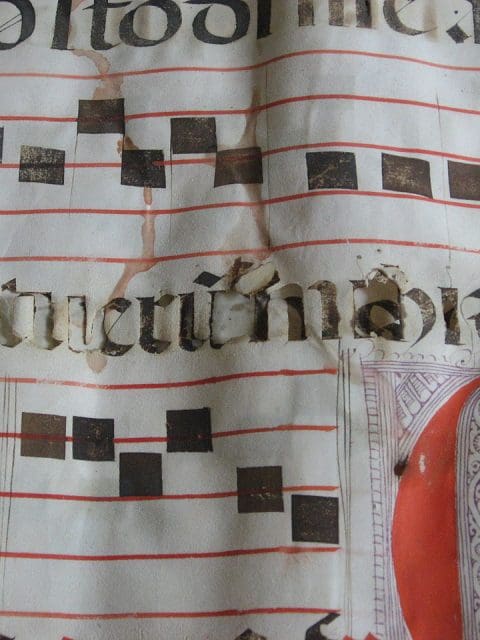

You see, any day you can speak is a day you can create music.

- If you write down the first melody that comes to your head, you have composed.

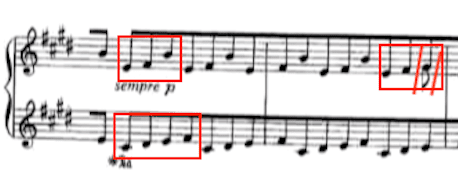

- If you spend 15 minutes tweaking 4 bars of music, you have composed

- If you sit down with your instrument and improvise for 2 minutes, you have composed.

- If you sing your musical imaginings to yourself in the shower or while driving, you have composed.

And though it’s true that some days we do need to step away from creating music, most days are not those days. Most days, you actually do have the time, energy, and even the desire to create in some small way.

But, too often, “some small way” is not how we imagine composing. Instead, we place impossible demands on it:

- “I have to complete this all at once.”

- “I have to do it right the first time.”

- “My unpolished improvisations do not count as composing.”

- “I need to map out the finished piece from the beginning and not deviate from my plan.”

- “What I write has to capture my initial inspiration.”

- “What I write has to live up to my artistic hopes.”

- “What I write has to become popular, financially successful, critically acclaimed, or connoisseur-approved.”

- “What I write has to be wholly original, ground-breaking, and boundary-pushing.”

Any one of these demands is a heavy burden—and they rarely come alone. Collectively, they are soul-crushing.

How Your Impossible Expectations Gaslight You

None of these Atlas-like expectations are good, healthy, or true. Yet they gaslight us into believing that we are the problem.

They make us believe that we must carry their burdens on our shoulders.

That unless we fulfill their demands, we are not real composers or good composers or successful composers.

That until we fulfill their demands, we are not yet good enough, not yet talented enough, not yet original enough, not yet disciplined enough, not yet famous enough, not yet respected enough, not yet anything enough to write music.

Is it any wonder, then, that part of you is trying to keep you safe from these feelings?

Ironically, that drive to keep you safe from those expectations only reinforces their outcome: you avoid writing music.

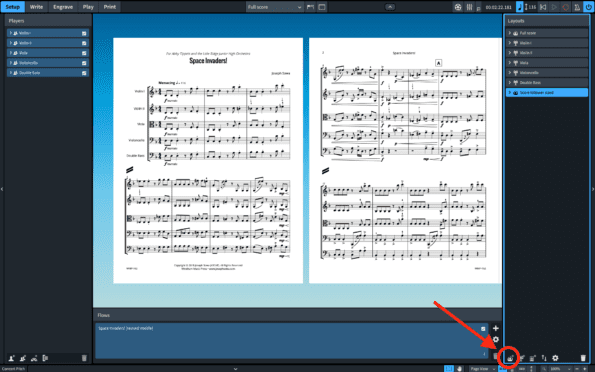

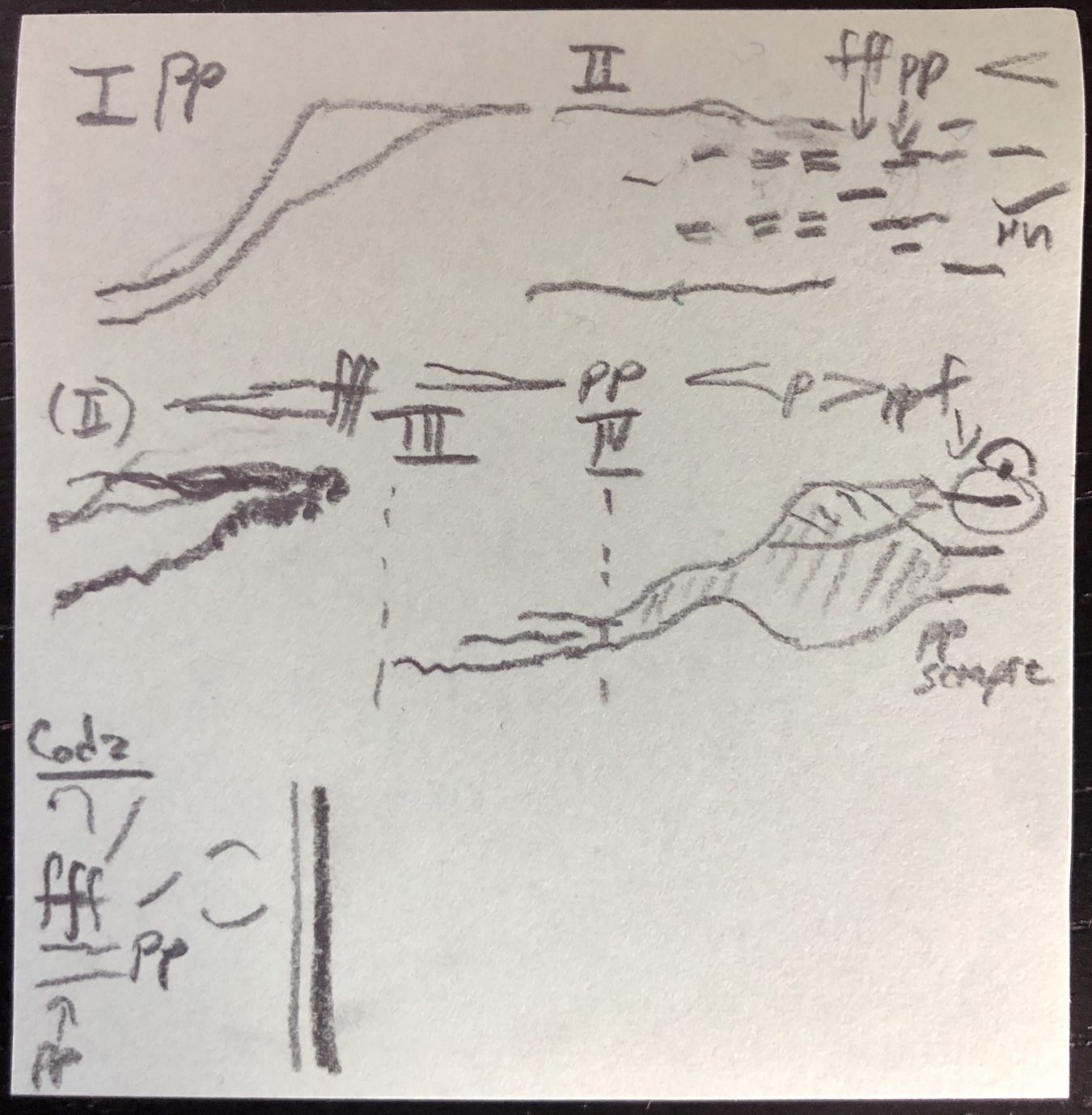

You and your impossible expectations (a selfie)

Truths to Hold On To

The first step, then, to composing today is accepting some uncomfortable truths—“uncomfortable” because the emotional abuse to which you’ve submitted under these expectations frightens you away from leaving them.

The foremost of these truths is as simple as it is powerful:

Your music matters because you matter.

And the second is just as profound:

You may not yet be as good of a composer as you hope to be, but, chances are, you are probably already a better composer than you need to be.

From these mantras come a whole host of counter-expectations:

- “I can complete this a little at a time—no effort is too small to count.”

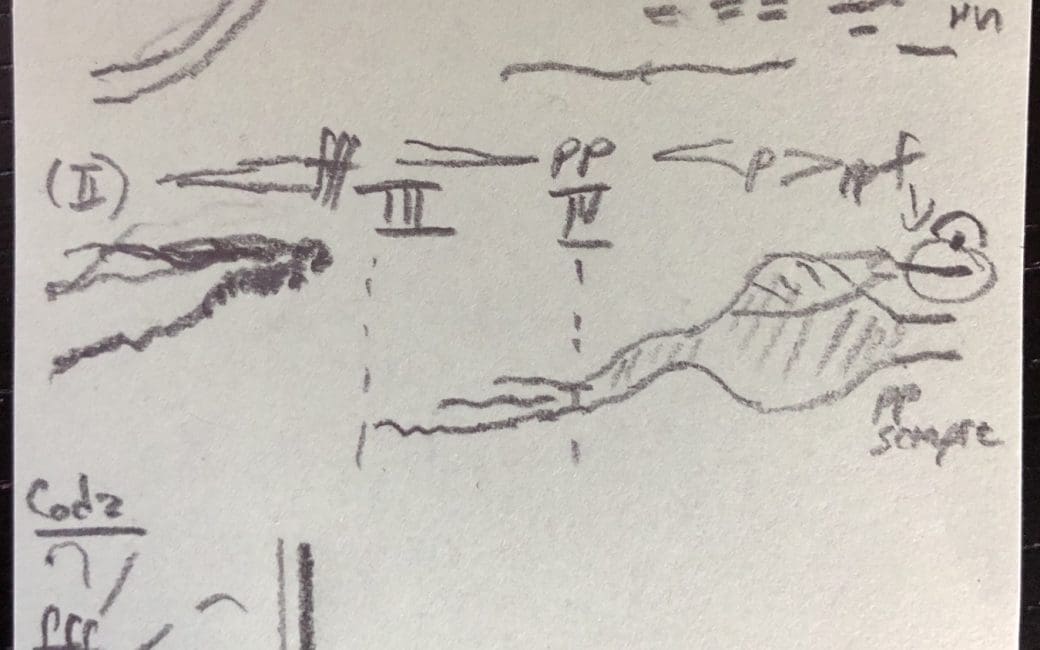

- “It only needs to be right at the end. Until then, I can revel in all the wrong roads and all the paths not taken.”

- “My unpolished improvisations are like ungut gems—they are the source of my polished compositions and a step I cannot skip.”

- “My understanding of the piece’s form and its extramusical associations will evolve as I write the piece.”

- “My initial inspiration, by definition, cannot be my goal. I can honor it, even as my work inevitably develops that idea in different directions.”

- “No single piece must or even can fulfill my artistic hopes.”

But how do you enact these expectations in real life? That is the subject of next week’s post.