If you’re like most composers, when you sit down at your desk or think about what you’re going to work on tomorrow, you probably think some variation of “It’s time to compose!”

You may get a little more specific, like “I need to write this passage” or “that movement” or “this cue.”

But generally that’s where it stops.

You leave it to your intuition to fill in the blanks of “what do I do next?”

Sometimes that works fine, but too often it leads us into an unnecessary panic of “Wait! I don’t actually know what I’m doing!”

Why farmers work smarter than composers

Consider the farmer.

They don’t wake up and say, “It’s time to farm!”

Even to those of us with minimal manual labor experience, that sounds silly.

Instead, the farmer has a clear routine:

- Feed the pigs

- Milk the cow

- Let the chickens out of the coop

- etc.

These are specific tasks.

They wake up. They know exactly what they have to do. They go do it.

They may be tired or have personal concerns, but they have no stress or worry over “What should I do next?”

But too often as composers, in our quest for originality and relevance, we grossly underplay just how repetitive our work actually is.

What composers can learn from farmers

👉 Here’s the secret: naming your composing tasks makes creativity easier and more fun.

Yes, I recognize that composing is a creative process.

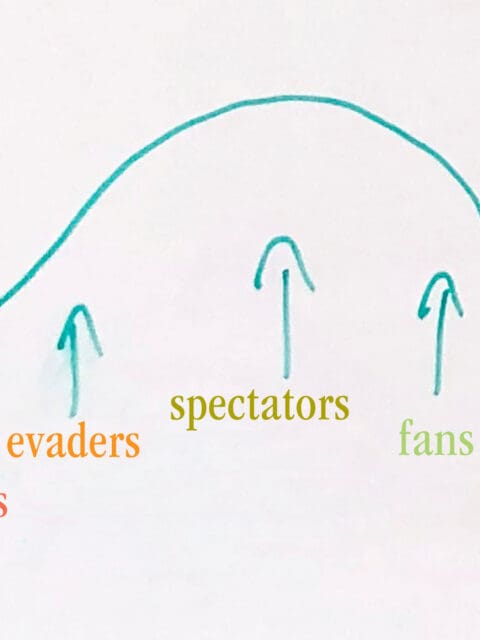

True, this means that your work rarely comes in the order of “A, B, C, D, E, . . .” but more often looks like “11, C, 2, 3, D, E, X, 8, 4, nine, . . .”

But just because the ordering of these tasks is often nonlinear does not mean that the tasks themselves are not discrete and definable.

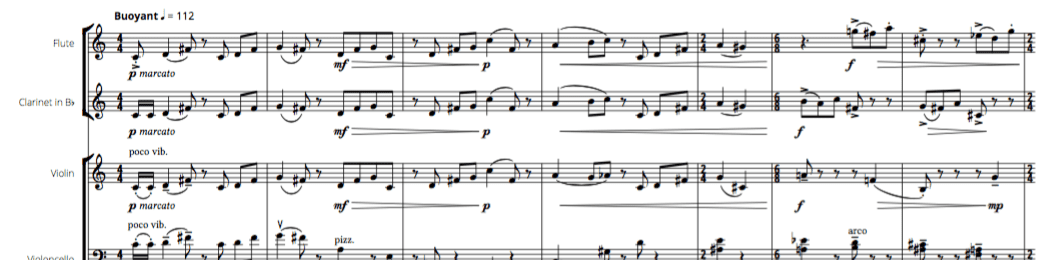

The composition equivalent to farm chores would be things like:

- Draft this 8-bar melody

- Devise 3 or 4 ways to harmonize it, then pick one

- Brainstorm several different ways of arranging it for the ensemble

- Execute that arrangement

- etc.

Because of mental simulation, when you can identify what you’re trying to do, it makes it so much easier for your intuition/your inspiration/the muse/whatever-you-want-to-call it to do its work.

So here is my invitation to you today:

- List out the composing tasks you know how to do.

- When it comes time to compose, identify 1–3 specific tasks you want to accomplish

Again, having these tasks does not mean you must work rigidly or robotically.

But it will help you work smart, like the farmer, and not constantly second-guess yourself.