So you’re writing a piece with piano accompaniment. You’re probably wondering, “What do I do with the piano?”

Many singers and non–keyboard-playing instrumentalists find it easy to come up with melodies, but when it comes times to create a keyboard accompaniment, they get stuck.

Even pianists themselves sometimes might feel a little overwhelmed.

Here are five tips to make it easier:

1. Embrace being in the background

At its most basic, an accompaniment creates the rhythmic and harmonic backdrop against which the melody is featured.

Like the backdrop of portrait photo, the accompaniment is meant to draw attention to the subject (i.e., the melody), not itself.

Photographers often do this by using dark backgrounds with subtle textures.

Composers create a similar effect by crafting accompaniments using short, simple patterns.

That pattern is then repeated verbatim, at least till the end of phrase. Often, it continues till the end of the song.

This may sound boring—but that’s the point. You want the listener to focus on the melody.

However intricate you end up making your accompaniment, you need first to embrace the idea that it must be at least a little boring.

2. Solve the harmony first

The most basic accompaniment pattern is half- or whole-note block chords.

Write this accompaniment to your melody first. If you know your chords, it shouldn’t take much more than five minutes to complete a rough-and-ready harmonization. (You can then spend more time tweaking the harmonies to your liking.)

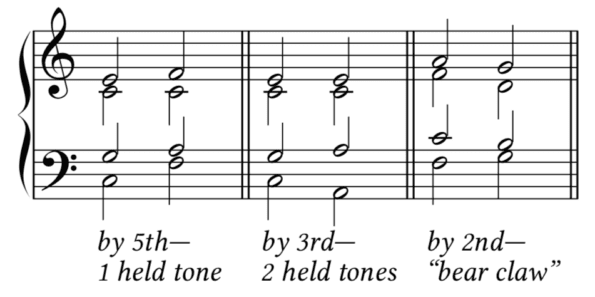

Once you’ve found the right chords, pay attention to how the notes in one chord lead to those in the next. This relationship between chords is called “voice leading.”

Chord progressions sound best when each note in the harmony moves by the shortest way from one chord to the next.

In four-part harmony, when the root of the chord moves by a fourth/fifth (e.g., C to F) or by a third (e.g., C to Am), the upper three voices can all move by step or remain the same. When the root of the chord moves by a second, the three upper voices must move in contrary motion to the bass, and one of your upper voices will leap down a third.

No matter how elaborate, every accompaniment implies chord-to-chord relationships like these. Even the the most intricate arpeggiations sound best when their notes move the shortest way from one chord to the next.

3. Know your options

The same way that accompaniments are inevitably a little boring, devising an accompaniment pattern is not a complex task. You don’t need to overthink this.

Most accompaniment patterns are either half a bar or one full bar long.

Each unit of the pattern presents a single harmony, and, absent a compelling artistic reason, the contour of this presentation remains constant.

Below are some common patterns:

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. You can just use these.

If you want further ideas, it is not plagiarism or “unoriginal” to borrow other composers’ accompaniment patterns. Some great sources for patterns include Chopin’s Nocturnes, Schubert’s song cycles, and Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words.

Contemporary song books of show tunes, pop standards, holiday songs, etc. will also have great accompaniment patterns you can lift and reuse in your music.

4. Change at the right time

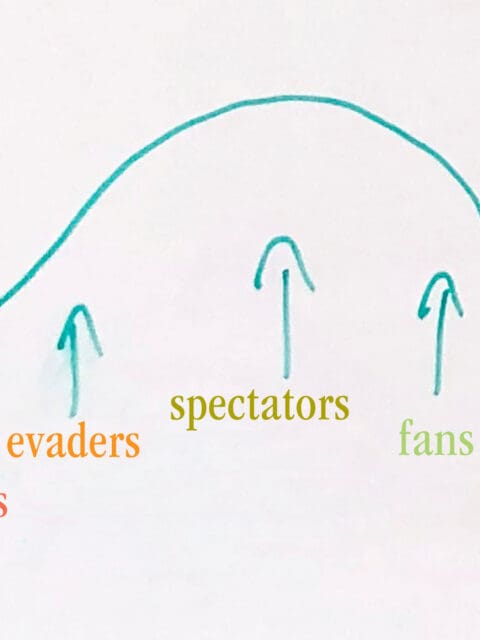

Although many songs get by with a single accompaniment pattern, you will often want to mix things up.

If you constantly change the accompaniment pattern or change it when you happen to get bored, you will draw attention away from the melody in a negative way.

The musical effect will be similar to watching a couple argue in public or seeing a piece of scenery fall down accidentally in the middle of a play.

There are three key places accompaniment changes are welcome:

- At the cadence of a phrase

- At the start of a new phrase

- Aligned with an meaningful word in the middle of a phrase

But remember, just because you can change accompaniment here doesn’t mean you should. Generally speaking, if the melody repeats from one phrase to the next, so should the accompaniment.

For instance, in a pop song, you would keep the accompaniment the same for the entire verse, then (if you want) you can change it at the chorus. But once you go back to the verse, you will go back to that original accompaniment.

Likewise, in a 32-bar AABA melody, you would keep the accompaniment the same for the first 16 bars, then (if you want) change it for the B-section, before returning to the original accompaniment for the final 8 bars.

5. Build on the basics

Once you can confidently execute these basics, you can begin to more your accompaniments more elaborate. Some common elaborations include:

- Incorporating harmonic breaks and turnarounds

- Using melodic motives to enrich the texture

- Adding countermelodies

- Writing intros and interludes

- Creating more interaction with the melody

- etc.

Together, these additional tricks will add richness and nuance to your accompaniments.

But if you aren’t there yet, don’t worry. Again, accompaniments are meant to be the background — and if you follow the first four tips, the real star of your arrangement, your melody, will shine through clearly.

Happy composing!

👉 Which of these tips are most helpful for you? Which do you want to hear more of? Let me know in the comments below or email me at joseph@josephsowa.com. I’d love to hear from you!