Tonality is a musicological debate about style disguised as a theoretical debate about pitch organization.

Whether it's Schenker's arrogant, narrow nationalism or Tymoczko's generous, imaginative catholicism, the debate around what defines “tonality” is, at its core, a question of repertoire.

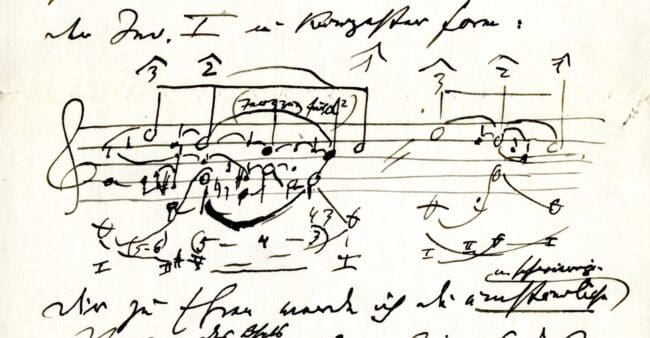

No one would argue that the music of Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms is not tonal. But what about William Byrd? Or Bull? Or, to go the other direction, Barber? Or Britten? To say nothing of Charlie Byrd or the Beatles?

Whether the music of these latter figures is tonal depends on who you ask. But whether it exhibits pitch organization is indisputable.

Hence, tonality is fundamentally a question about style, not pitch organization.

Style is a red herring for composers

Learning to distinguish “tonal” from “atonal,” “post-tonal,” “pre-tonal,” or “extended tonal” music carries about the same relevance as distinguishing between sub-genres of death metal. It’s not useless—but it doesn't describe really how the music works. It mostly just identifies its stylistic markers.

In other words, “tonality” is an elaborately justified label.

For composers who want to know how music works, such stylistic labels are a red herring. Style can tell you what combination of features will produce a particular “sound,” but they don’t actually show you how it works. As Charles Ives quipped, “What has sound got to do with music?”

Milton Babbitt affirmed Ives’s quip when he asserted, “Nothing gets old faster than a new sound.”

Lest you think this bias against “sound” is some avant-garde fetish: First, remember how much avant-garde composers focused on sonic innovation. Second, put Babbitt’s words in the mouth of any pop music agent or producer, and you’ll notice that they fit right at home there, too.

Like cars and smartphones, the value of unique “sounds” quickly depreciates.

Style tells you little about musical excellence. Instead, it is a proxy for cultural power and relevance. Again, this is not a useless consideration—but it is, at best, tangential to the question of pitch organization.

Musicians can organize pitch in a lot of ways

In truth, “tonality” comprises a detailed collection of pitch strategies that musicians have used in various combinations and emphases. Many of these strategies carry over into music that exists at the edges or beyond the boundaries of what scholars consider “tonal.”

Among other concepts and approaches, they include assumptions about

- octave equivalence

- tuning and enharmonic equivalence

- structural hierarchies

- distinctions between consonance and dissonance

- the qualities, spellings, and inversions of different intervals and chords

- the functional equivalence of chord inversions

- harmonic consistency

- harmonic syntax via scale-degree function or hypermetrical placement

- harmonic and voice-leading schemata

- the usage of different scales

- the prevalence of stepwise motion generally in melodic lines and strongly in harmonic voice leading

- melodic shape via step progressions, rhythmic permutations, or hypermetrical placement

- melodic structure via rhythmic motives, pitch motives, and pitch contours

- the harmonic implications of all melodic lines

- the functional distinction between the bass line and upper voices

- degrees of formal articulation indicated by coordinated of harmonic and melodic gestures (i.e., cadences and pitch centricity)

Despite being almost 20 items long, this list is hardly an exhaustive catalog of pitch organization concepts and approaches. What distinguishes different styles is how they remix these principles.

Some pieces use many of these strategies. Others use only a subset of them. Still other pieces use different pitch strategies entirely.

Though many pieces contain all of these strategies, no single piece can be said to exemplify all of them.

Focus on the effect, not the label

Furthermore, none of these strategies or their applications is intrinsically “excellent” or “superior.” But noticing them allows musicians to hone their discernment about how specific pieces create the musical effects they do.

For instance:

- How can Debussy get away with writing parallel fifths?

- How does Beethoven write an hour-long symphony that isn’t boring?

- How does Rachel Portman write an hour-long soundtrack that isn’t boring?

- Why does Byrd’s counterpoint feel different than Bach’s and different again from Bartók’s?

- How does Mahler give you goosebumps?

- How does John Coltrane create the luminous sheen in his solos?

These questions do tell you something about style—but when you go beyond merely labeling these features to describing their relationships to key moments in a specific piece, that’s when you really start to understand how music works.

That’s when you can discern not just why Debussy’s style is different than Clara Schumann’s (for instance), but what the music is doing to create its unique states of being.

Thus, the most pertinent analytical question for composers is not “What style is this piece and why?” or even “What specific choices did x composer make?” but “What is the effect of these choices?”

P.S.—If you want to dig further into these questions, here are some key books to check out: Gjerdingen, Harrison, Huron, Straus, Tagg, Tymoczko.

Don’t Miss Next Week’s Post

Sign up to stay in the loop about my music—and ideas for your own composing!