[Ed. — After publishing this post, I discovered that many readers were misreading my intent and were unfamiliar with the background of my critique. Accordingly, I added and tweaked several paragraphs below and wrote an additional post. New readers may want to start by reading that subsequent post, “How Composers Used To — and Could — Be Trained.”]

You may think as I did — when you took AP music theory, or completed the standard college theory core, or watched a theory video on YouTube — that you were learning how music works.

As an aspiring composer, you may have even hoped, “If I learn music theory, I’ll know how to write music.”

Unfortunately, that’s not true.

What Music Theory Actually Teaches

Unless you were unusually well-informed as a young composer and happened to win at “theory-instructor roulette” (or got deep into weeds of the grad-level theory discourse), it would be easy to infer — incorrectly — a certain set of assumptions about what theory offers.

Because learning theory involves writing and analyzing music, it is natural to assume you were learning composition on some level. Unfortunately, such assumptions often reflect more your own musical goals than they grasp the pedagogical objectives of most textbooks, university curricula, and online sources.

The music theory core, as it is commonly taught, does three things. It —

- Explains staff notation and music fundamentals (e.g., meter, rhythm, intervals, scales, chords)

- Describes what is normative to a specific repertoire, with an emphasis on harmony

- Gives dumbed-down recipes for how to recreate those norms

For the vast majority of university and online courses, that’s about it.

Now, a few courses (typically those focused on a film music, jazz, or songwriting) do go one step further: showing you how to recreate several different musical styles.

But even when it involves some composing, learning theory is fundamentally a descriptive enterprise.

Theory mostly teaches you how to talk about music, not how to make it. This is, of course, useful, but there can be a yawning gap between understanding music conceptually versus being able to create it practically.

As Robert Gjerdingen put it, the modern university theory core is like taking a course in space exploration. You end up able to discuss the subject and perform some rudimentary tasks — but that doesn’t make you an astronaut.

The Glaring Holes in Standard Music Theory

For those hoping to learn how to write music, the common theory curriculum has some glaring holes:

- Despite melody being central to much music written today, few universities or online courses rigorously teach how to write a melody. True, they often teach general melodic forms and features (e.g., sentence form and high points), but only occasionally how to create the things that go into the formal boxes and how to control their features.

- Likewise, melody and accompaniment has been hands down the most common musical texture of the past 300 years, yet many theory courses never teach that skill — instead, focusing on how to write approximations of chorales.

- Regarding harmony, most universities and online courses teach far less than it seems because they teach a grammar of harmony, but not a vocabulary of specific harmonic gestures and their usage. As with melody, students are then taught formal boxes that can string together these grammatical utterances. The result is like teaching someone how to make grammatically correct English words, sentences, and paragraphs — while having only the haziest understanding of what the words actually mean.

And then there’s the big elephant in the room: How does music take listeners on a journey that gives them goosebumps or takes their breath away? The common curriculum avoids the question entirely, even though solid scholarship exists on the topic.

And then there’s the big elephant in the room: How does music take listeners on a journey that gives them goosebumps or takes their breath away? The common curriculum avoids the question entirely, even though solid scholarship exists on the topic.

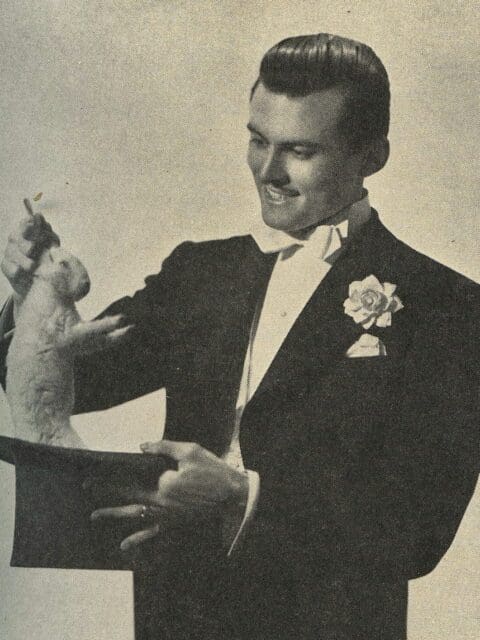

In essence, music theory gives composers a rabbit and a hat . . .

And then expects them to figure out how to create the magic on their own (or “in a different course”).

Why Theory Training Can Leave You Frustrated

Is this theory’s fault? Of course not.

But if you don’t understand what the theory core is trying to do, it is easy to become confused and frustrated.

As a result of these misunderstandings,

- You end up writing vanilla, run-of-the-mill music . . . and you don’t know how to spice things up.

Why? Because, by design, theory teaches you how to create what’s common and general, not unique and specific.

- You come to believe that excellence is a result of “geniuses breaking rules.”

Why? Because when you try to break the rules you were taught, your music just sounds worse.

- You feel like you’re reinventing the wheel every time you compose.

Why? Because the rules you were taught work were the equivalent of short-order recipes for specific styles. You were never taught how to make bespoke pieces in different or original styles.

- You feel like your music has to sound a certain way to count as “original.”

Why? Because most composition programs replicate the same issues from the theory core of focusing on norms and recipes rather than mastering possibilities and principles. The only difference is that, instead of passing tones and augmented-sixth chords, now those recipes include pitch-class sets, multiphonics, and bowed crotales.

So if you feel frustrated as a composer . . .

If you feel like something has been missing in your musical education . . .

You are 100% correct.

Don’t Miss Next Week’s Post

Sign up to stay in the loop about my music—and ideas for your own composing!

And then there’s the big elephant in the room: How does music take listeners on a journey that gives them goosebumps or takes their breath away? The common curriculum avoids the question entirely, even though

And then there’s the big elephant in the room: How does music take listeners on a journey that gives them goosebumps or takes their breath away? The common curriculum avoids the question entirely, even though

Some people do already tell you this about music theory. In so much as ‘Music Theory’ exists at all.

There is a kind of Venn Diagram of ‘concepts that are universal’ and ‘why this piece is beautiful’. The areas have almost no overlap whatsoever. Still, you can’t just look at labels, and you also can’t just rhapsodize about pieces that move you. The interesting work is to try to walk between the two. A parallel dialectic is that music is universally part of the Human experience and, at the same time, no two of us seem to hear it the same way. We love it generally and specifically like different things. Trying to explain how that works should be fun, both for the teacher and the student.

Agreed. Those differences between people is where a lot of the magic actually lives. And the fun of it, rather than fitting a piece of music into one theory, is using any useful theory (or even just lucid observations) to analyze music — not labeling, but really digging into “What stands out to me about this piece? Why? How can I explain it to you?” And then “What are you hearing? What moves you?” etc.