I recently explained how Classical musicians understood harmony in terms of characteristic gestures. For my first demonstration of this gestural approach to harmony, I present the Latter-Day Saint hymn “Father in Heaven, We Do Believe.”

In this post, I’ll identify the gestures that compose the piece and how they’re connected. On Thursday, I’ll show how these gestures are elaborated and how all these elements work in concert to make the arrival on “we receive” so striking.

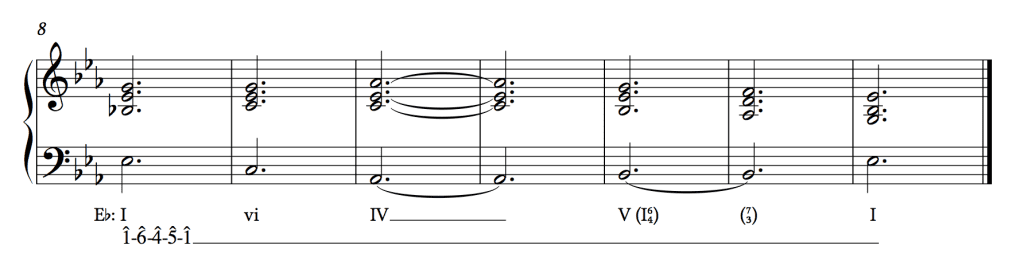

But first, the original hymn:

What gestures compose the piece?

Though structured into two phrases, the hymn actually consists of three harmonic gestures.[1. I’ll eventually post my dictionary of harmonic gestures, but for now, I’ll provide as-you-need-it explanations in the footnotes.] The first phrase contains two:

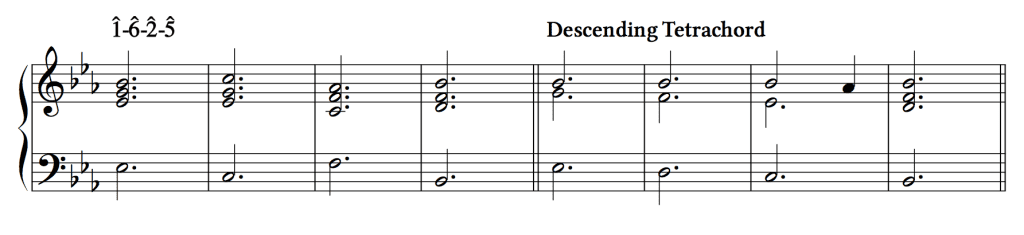

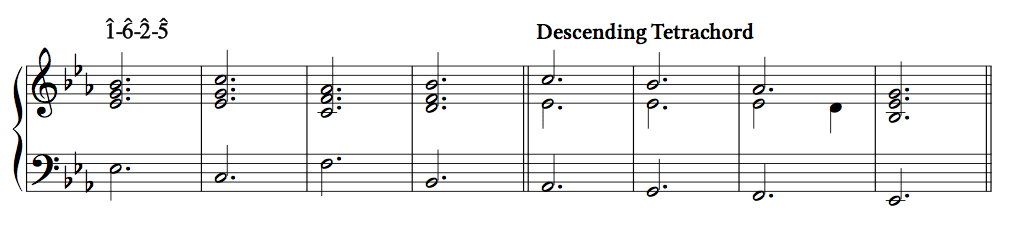

- a 1-6-2-5[2. Hyphenated numbers refer to structural scale degrees in the bass.] (from the Circle of Fifths family)[2. The diatonic Circle of Fifths being 1-4-7-3-6-2-5-1 (excerpted portion underlined).]

- and a descending tetrachord.[3. Usually 1-7-6-5 or 4-3-2-1.]

The final phrase is a single gesture: a 1-6-4-5-1 (from the Bergamasca family).[4. The Bergamasca is the familiar 1-4-5-1 progression. As this gesture and the Circle of Fifths demonstrate, gesture families contain members that both add to and take away from their characteristic form.]

How are they connected?

The succession of 1-6-2-5 with the descending tetrachord is interesting because they have a similar shape and voice leading. Both descend a fourth over four structural pitches. Both often arrive on the dominant.

This close relationship lends this thread of gestures a subtle sense of repetition. What makes it so elegant is that composer Jane Crawford doesn’t use the descending tetrachord in the major, of which there are two possibilities:

Crawford doesn’t use either of these typical options. Instead, she begins it in the relative minor, connecting the gestures through a deceptive resolution from the first’s dominant to the second’s transposed tonic:

The second phrase’s immediate return to E-flat isn’t jarring, first, because it occurs at a phrase boundary, and more importantly, because the soprano note remains constant between the two phrases. That the second phrase repeats the first’s starting two measures almost verbatim also smooths this transition and sets up the striking arrival on “we receive,” which I’ll discuss on Thursday.

Notes

Don’t Miss Next Week’s Post

Sign up to stay in the loop about my music—and ideas for your own composing!