As you may have heard, the PRISM Quartet’s latest album, Surfaces and Essences, came out this past week. I’m thrilled that my piece “Motion Lines” was on it—along with a bunch of other great music by Christopher Biggs, Victoria Cheah, Viet Cuong, and Emily Koh.

First things first, if you haven’t listened to the album yet, go do that!

Then, be sure to purchase it from Apple Music or Amazon and support the PRISM Quartet.

You can also find the sheet music here.

Now, Join Me Behind the Scenes

That’s the shiny professional part. I wanted to take you behind the scenes, though, to give you a peek at what the composing process was like. Ever since 2004, I’ve kept a steady journal. Every week I write something. Most weeks I write a lot more. So I dug into my journal to pull out some scenes from the process of writing for and collaborating with the PRISM Quartet . . .

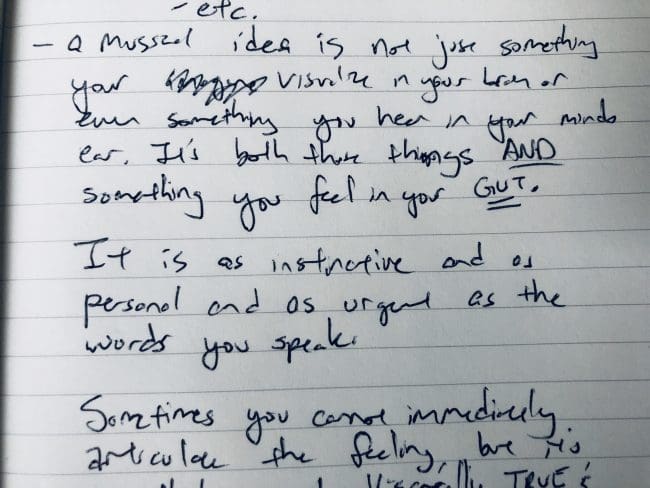

From the Project Notes: (Undated)

For every composition I write, I keep a text file of musical ideas, revision notes, possible titles, etc. Here is the original outline I wrote for the piece:

And here’s me talking more about these notes on YouTube:

While Composing: December 6, 2016

I didn’t end up writing a lot about the composing process itself, but hands down (pardon my pun, as you’ll soon see), this was the most eventful thing that happened during it: my first time ever getting stitches.

“I got stitches today after proving how sharp Cutco knives are while cutting an apple. Oops. The cut didn’t seem bad, but it soon became clear that the band-aid was no match for it. So on went a gauze pad over the band-aid and over I went to the urgent care center. $20 and an hour later, I had my stitches. . . .

“After coming home, I ate some, and eventually took a nap. I couldn’t focus. When I woke up, I eventually composed some until I went to the movie (Dr. Strange) with some friends.”

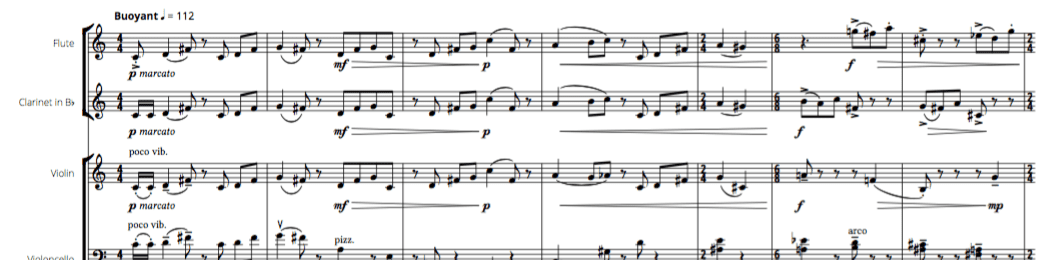

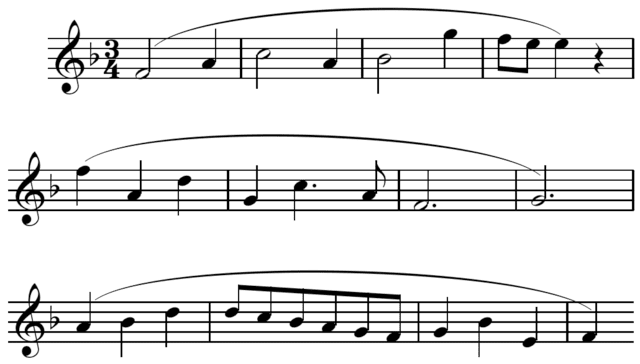

In addition to keeping a journal, I also save backups of my work every day. So I can show you, here, after getting stitches, is what the piece looked like by the end of December 6:

At the Rehearsal: January 27, 2017

Most rehearsals of new music sound like a partially carved statue looks. With the PRISM Quartet, the experience was different:

“The rehearsal went well. I was delighted that ‘Motion Lines’ is sounding as I had hoped it would. It’s fun to hear it first shaping into something musical. It’s funny, too, how there’s totally a sax player personality, and they all have it, refracted through the lenses of their individual personalities.”

I only wish I were cool enough to have the sax player personality.

After the Concert: January 29, 2017

In addition to how much I loved the PRISM Quartet’s performance of my piece, something else that stood out was how different the pieces were that we Brandeis students wrote for them. Despite this diversity of styles, PRISM knocked all the performances out of the park.

“The concert was fantastic. My piece got a great performance, and I received some really positive feedback from Eric and Davy as well as from my peers, including Richard, Talia, and Jeremy. Davy’s piece ‘Compass,’ which followed mine and concluded the concert, was easily the most like mine. Jeremy’s was the next closest, having a linear narrative, but its surface was way more sound- (rather than harmony-) focused, like the other five pieces. I liked them all a lot. As I was telling Talia and Alex after the concert, I find my peers really inspiring because they all do such different things at such a high level. That and they’re friendly, articulate, and supportive.”

Afterword

After the concert, I assumed that was that. I had a great time working with the PRISM Quartet, and they made a great recording of my piece. But ten months later, Matt Levy emailed me asking if they could include “Motion Lines” on a forthcoming album. Of course, I said yes.

Although the album started in 2017, most of my contributions to it—preparing an initial mix, putting together program notes, and so on—didn’t happen until the second half of 2019. Almost all of that correspondence happened through email, and, well, now you can see and hear the result.

If you haven’t yet listened to the album, go check it out at all the usual places: Apple Music, Amazon, Spotify, PRISM’s website. Then, if you want the the sheet music, it’s available here.