Composing is not magic. It is a behavior.

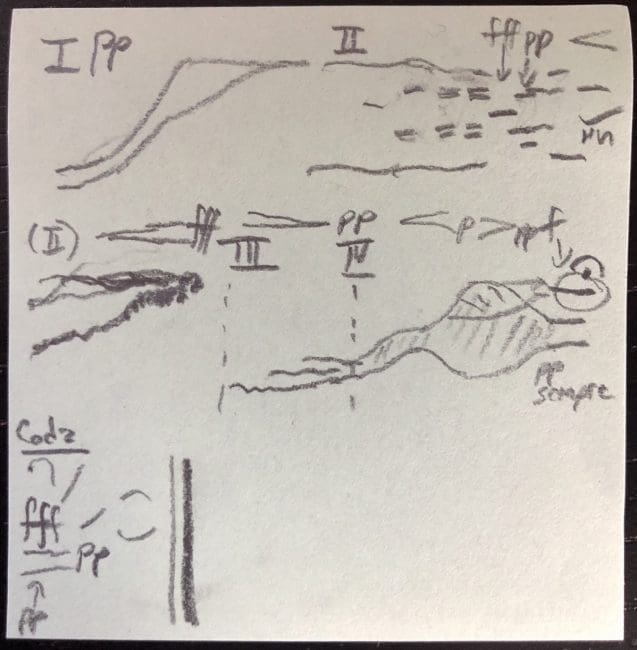

More specifically, composing is a collection of actions and behaviors—improvising, sketching, notating, revising, etc.—that may lead to a deliverable outcome—a printed score, a live performance, a mastered track, etc.

Beneath these behaviors lie deeper motivations.

Some people compose to make money. Others compose to have fun. Or to secure tenure. Or to get into grad school. Or to see their name on a Hollywood movie poster. Or to fit in with their peers and mentors. Or to impress critics and gatekeepers. Or to make fans. . . .

Any number of these aspirations can sit behind why you compose—but they still aren’t your deepest reasons.

Behind these aspirations, what you really want is to feel economically secure. Or satisfy your thirst for learning. Or secure your belonging in a particular tribe. Or find love. Or use your musical excellence as a proxy for your personal worth. Or feel like your life matters to someone else. . . .

Put simply, you and I compose because we want to ensure our physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs are met.

These intangible drives are the bedrock reasons people do anything. Their lack of fulfillment is what inspires worries, insecurities, self-doubt, and self-destructive behaviors.

Stop Making Composition Hard

Helping people find mature, healthy, and flexible answers to these ultimate concerns is for psychologists and spiritual advisors.

I am a creative coach, and as such, my job is to point out one simple truth:

You do NOT have to master your deepest motivations in order to compose.

And thank goodness for that. Self-knowledge is a lifelong pursuit. If it were a prerequisite to action, you would never be ready to do anything.

Moreover, you do NOT have to pursue some career or social strategy in order to compose.

Though such strategies are useful, no single compositional behavior can ever accomplish a career or social goal. In fact, most compositional actions you take have zero bearing on whether the Los Angeles Philharmonic commissions you or Princeton offers you tenure.

Most of all, you do NOT have to complete your printed score, master your track, etc. every time you sit down to compose.

Focus on Actions, not Outcomes and Aspirations

Indeed, it’s not possible to achieve deliverable outcomes every time you compose.

As behavioral scientist BJ Fogg explains, “A behavior is something you can do right now or at another specific point in time. You can turn off your phone. You can eat a carrot. You can open a textbook and read five pages.”

In compositional terms, you can improvise an 8-bar melody. You can notate that melody. You can write out three different harmonizations of it. You can draft two different arrangements of those 8 bars.

Any one of these tasks takes less than 20 minutes for even an intermediate-level composer (let alone a professional).

Fogg continues, “In contrast, you can’t achieve an aspiration or an outcome at any given moment. You cannot suddenly get better sleep. You cannot lose twelve pounds at dinner tonight.”

In other words, you cannot suddenly write better counterpoint. You cannot secure tenure in one morning’s composing session. You cannot gather a wide following with one email blast.

Most pertinently, for composers indoctrinated in Romantic/modernist notions of musical “excellence” (as we all are to some degree), you cannot write innovative music—or even simply deliverable music—without iterating your initial ideas.

Musical excellence is, at best, an outcome (Fogg: “[something] measurable, like getting straight As second semester”), but far more likely, it is an aspiration (“abstract desires, like wanting your kids to succeed in school”).

Excellence is NOT a compositional behavior. It is not something you can do “at any given moment.”

This Is Why You Hurt Yourself

“You can only achieve aspirations and outcomes over time if you execute the right specific behaviors,” Fogg concludes.

These “right specific behaviors” do not depend on any aspirations and deliverable outcomes:

- The deliverable outcome of compositional behaviors is not essential to doing those behaviors.

- Achieving your career or social aspirations is not essential to doing compositional behaviors.

- Fulfilling your psychological drives is not essential to doing compositional behaviors.

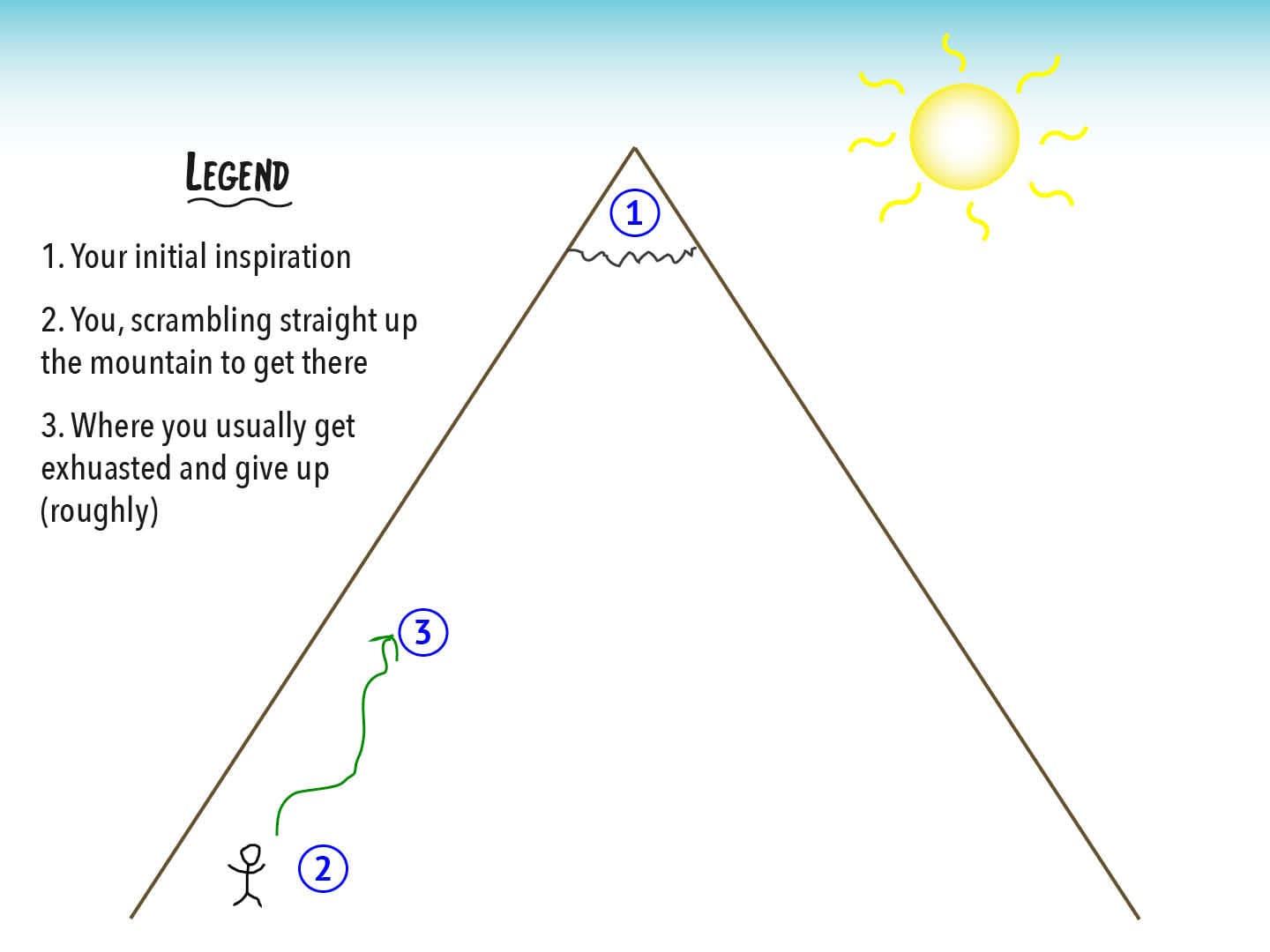

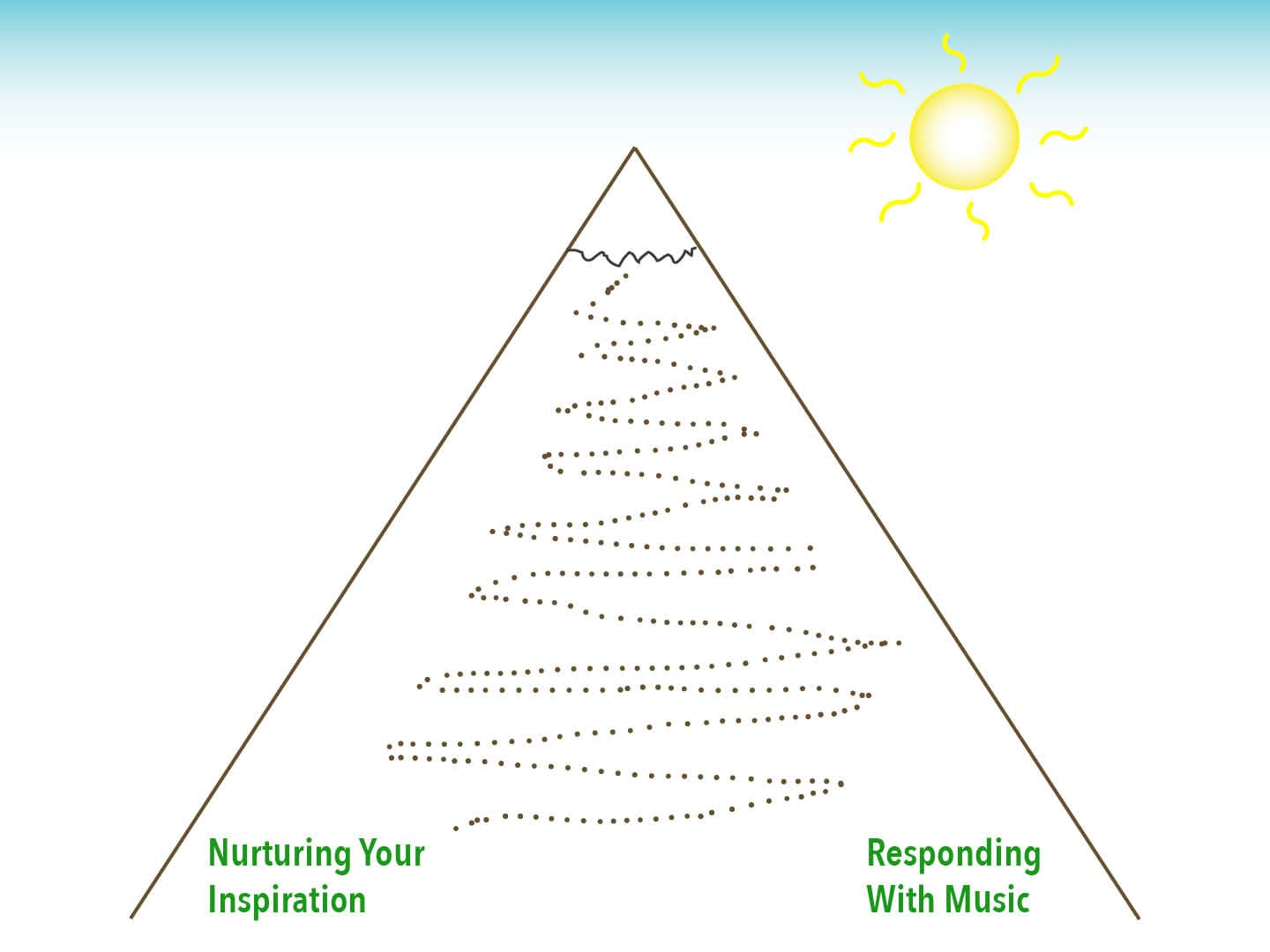

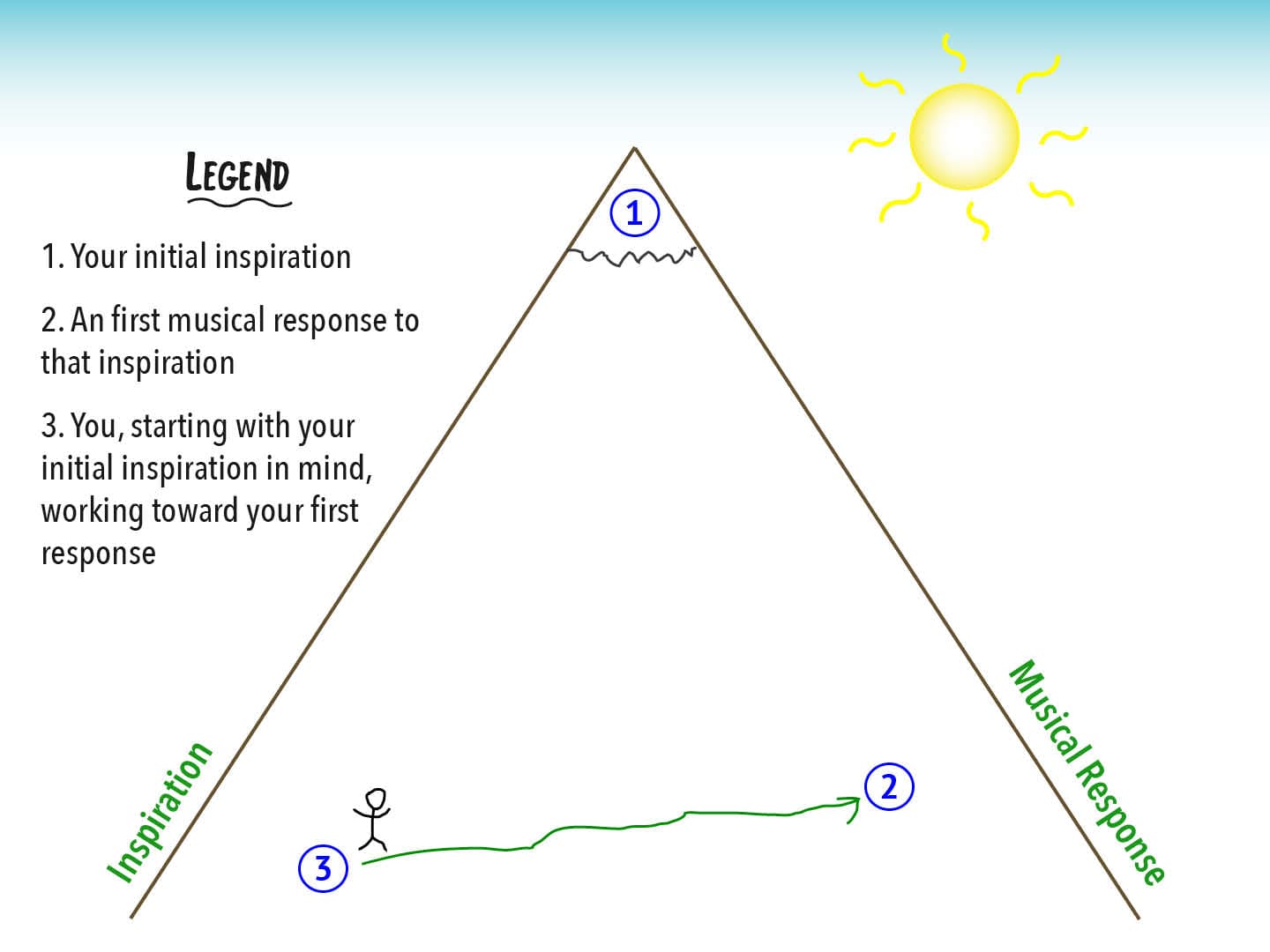

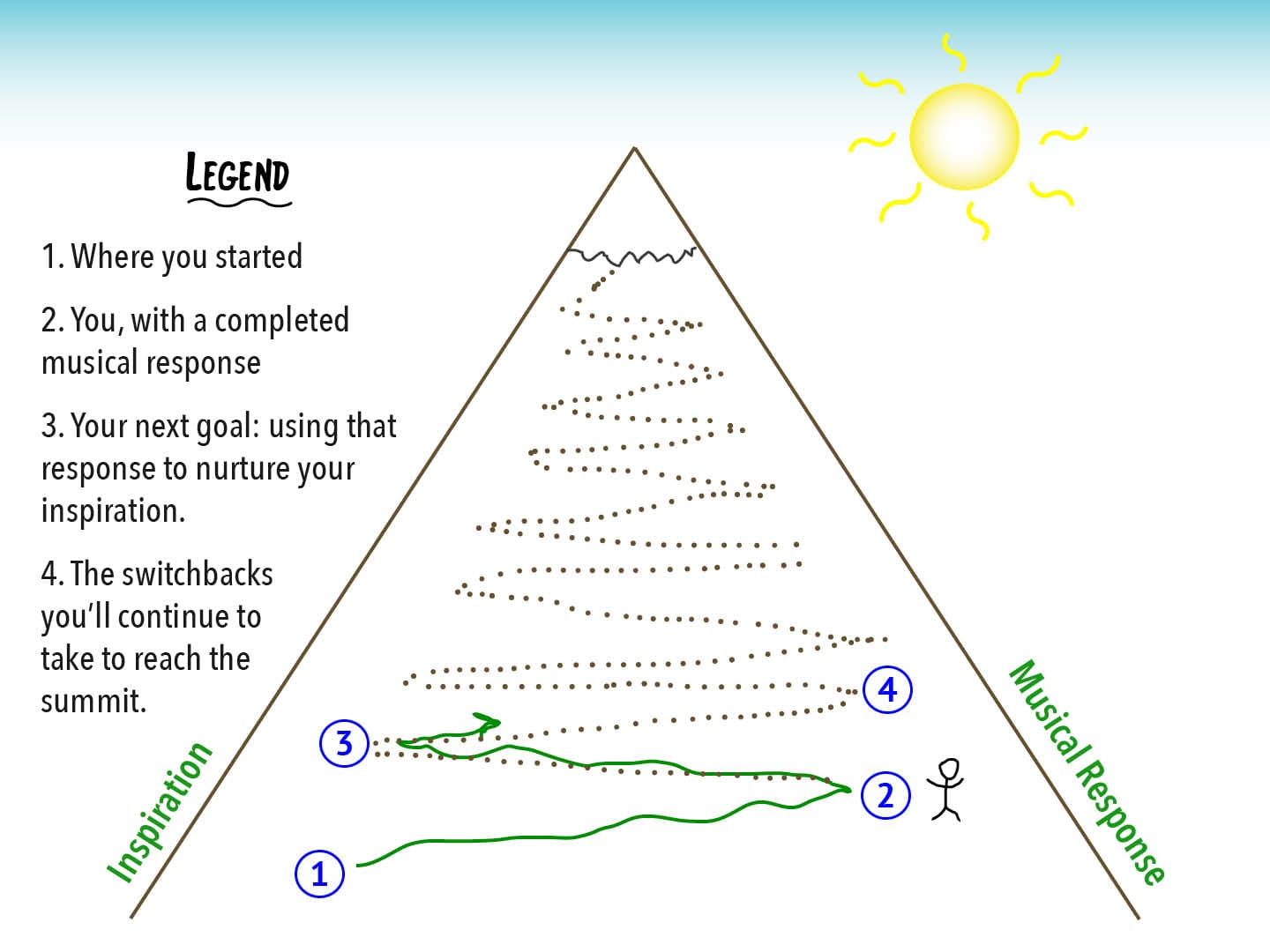

So, if you want to compose today, first, recognize that any compositional behavior you do is just one step toward your deliverable outcomes or aspirations.

Think of your compositional actions like a bed of nails and the composition process like laying on that bed.

When your pressure is spread across hundreds of nails, you can lay (relatively) comfortably without injuring yourself. But if you place all your pressure on one or two nails, you WILL hurt yourself.

Likewise, any given 20 minutes of composing cannot support the full weight of your artistic ambitions. If you try to force it, you will injure yourself emotionally.

We’ve all been there . . .

The Process Keeps You Safe

It was never the pressure you placed on yourself that took you from blank page to finished score, because that pressure represents an aspiration or a psychological drive.

Aspirations and drives are not behaviors. They are stories. They cannot do anything.

So, second, trust the process.

Most music you write will take at least 5 hours to complete. That time span represents at least 15 composing actions.

If you do even one composing action today, it will likely have dozens, if not thousands of fellows.

So just choose one and do it.

Every action you take will help you understand your piece better. The results of any single action need not be visible in the final product.

In time, all your little actions will add up. They always do.

“But,” you protest, “That’s not inspiring! Doing some arbitrary behavior feels pointless. How can I know which compositional behaviors I should do next?”

Stay tuned. That is the subject of my next post.