FACT: In classical music, chord progressions are a byproduct of contrapuntal gestures. As a Paris Conservatory professor once said, “Harmony is a fairy tale told about counterpoint.”

This is no “chicken or egg” question.

For more than 500 years, beginning with medieval chant, European musicians thought in terms of melodic lines. It wasn’t until 1722 that they started talking about “chords” as we do today. (And it took a further 200 years for the modern concept of “chord” to predominate.)

Instead, they thought of “harmony” as the intervallic relationships between melodic lines.

In this conception, any single vertical sampling of intervallic relationships (what we’d call a single “chord”) was . . . kind of meaningless.

Isolating a single “chord” would be like looking at an extreme close up of an eye or nose, rather than seeing a person's full face, let alone their entire body.

For the pre-20th century musician, harmony only made sense in the context of melodic fragments.

In fact, young musicians’ “theory training” consisted of them learning how to infer the missing parts from a single melody.

Over the course of hundreds of “partimenti” and “solfeggi,” they learned which bass line fragments went with which soprano line fragments.

They learned how to string these melodic fragments together to make phrases, how to embellish them with “diminutions,” and how to flesh out the texture with additional voices.

This is why Bach could look at a fugue subject cold and immediately understand its contrapuntal implications. This skill did not mark him as a genius; it marked him as competent.

This is why Handel could write The Messiah in a month or Mozart could write the overture to Don Giovanni in one night. These feats did not mark them as uniquely inspired; it marked them as fluent.

All their lesser known peers did the same things. Even today, these are skills anyone can learn, not gifts for the few.

The 20th century’s greatest composition teacher, Nadia Boulanger, created a veritable “who’s who” of composers by teaching these contrapuntal patterns to Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, Quincy Jones, Astor Piazzolla, and dozens of other luminaries.

Lest you think this is just a fusty classical music thing, look at the highest echelons of jazz. Take Jacob Collier. He has perhaps the most imaginative harmonic ears of any musician of the past 50 years.

In interviews (and you should go listen to him—he’s both fascinating and utterly charming), Collier doesn’t talk about “chord progressions”; he explicitly talks about voice leading (i.e., counterpoint). Different pedagogical tradition. Same musical concern.

This is why in the Wizarding School for Composers I teach composers these contrapuntal patterns.

Not because we’d have time in four months for students to master them. (Hard truth: That mastery takes almost a decade.*)

But because composers can write music FASTER and MORE CONFIDENTLY when they can even just begin to hear these patterns and understand the thought process behind them.

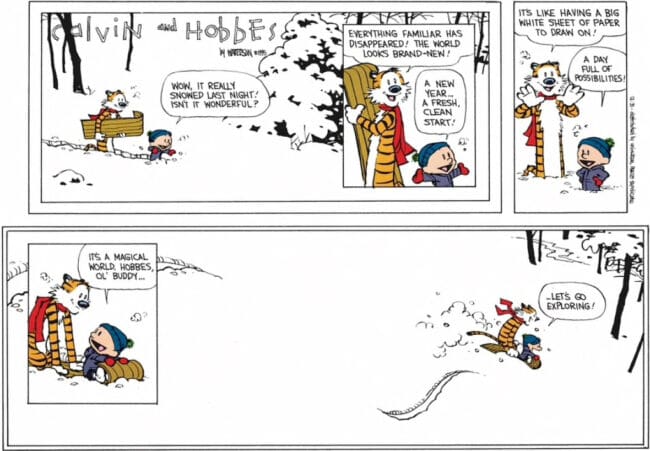

Composers who learn to think in contrapuntal gestures become far better equipped to write richly detailed music than those who only hear chord progressions, those who think that, like snowflakes, counterpoint lacks any underlying patterns, those who try to rediscover the patterns for themselves, and those who think the patterns somehow don’t apply to their pitch-based music.

Whatever style you write, learning contrapuntal gestures will improve your music and make composing much easier.

*) This long learning curve is why you probably haven’t heard of “contrapuntal gestures.” In the 20th century, as music theory became more focused on training amateurs and college students, contrapuntal gestures were brushed under the rug. Amateurs and college students don’t want to spend a decade learning counterpoint, so teachers started looking for quick and dirty solutions to teach harmony. Over time, most of the English-speaking world forgot about the earlier tradition. Now, if you know where to look (figured bass), its vestiges are still there, but many teachers don’t seem to know why those vestiges are there or how to unlock their power.