I’d had it with music.

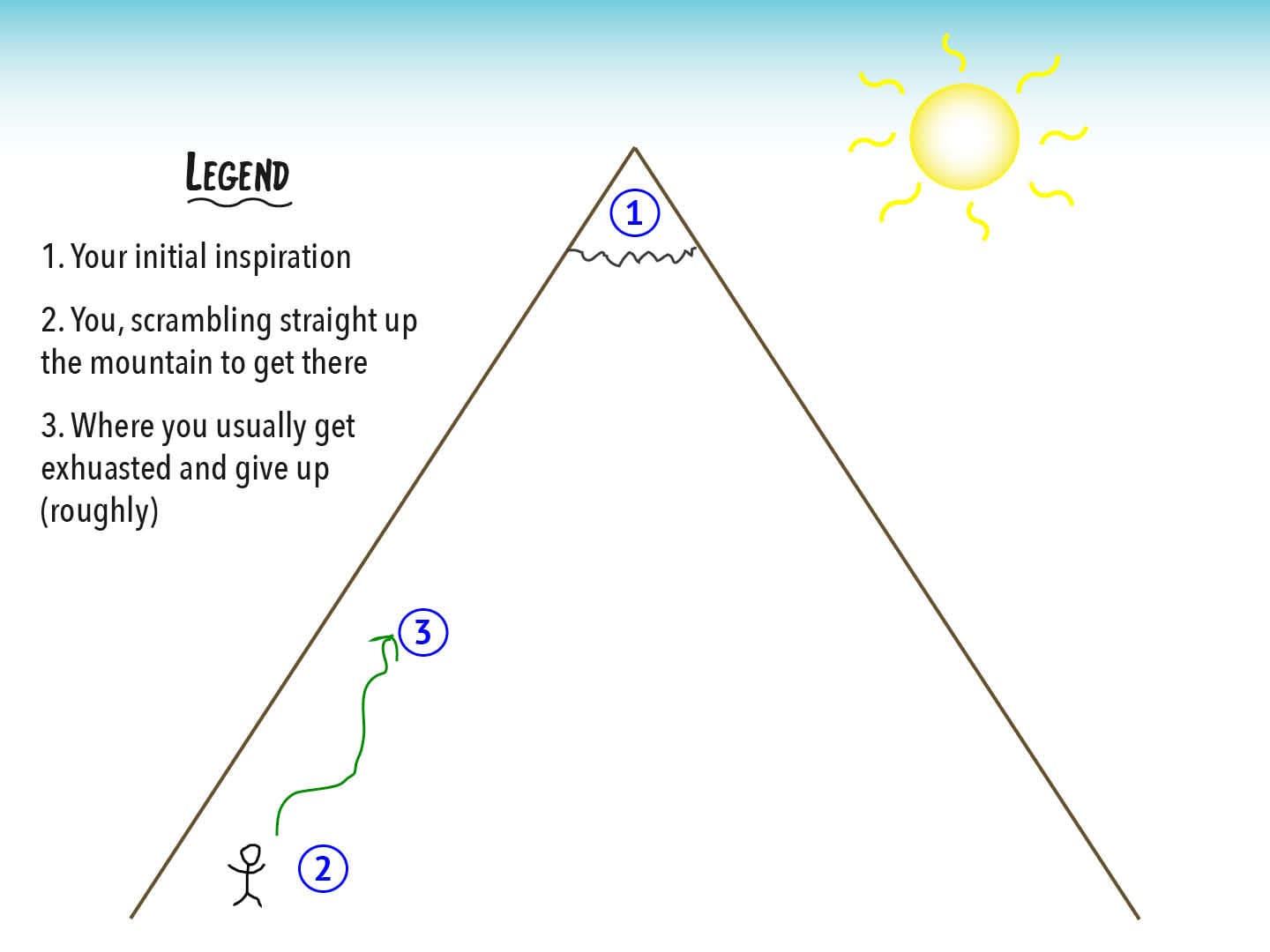

Composing was too hard, too frustrating.

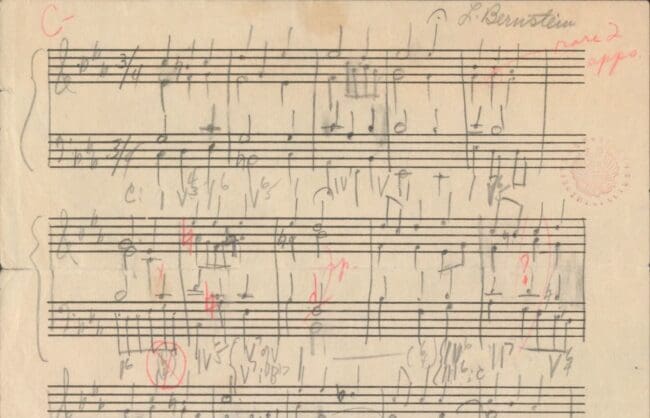

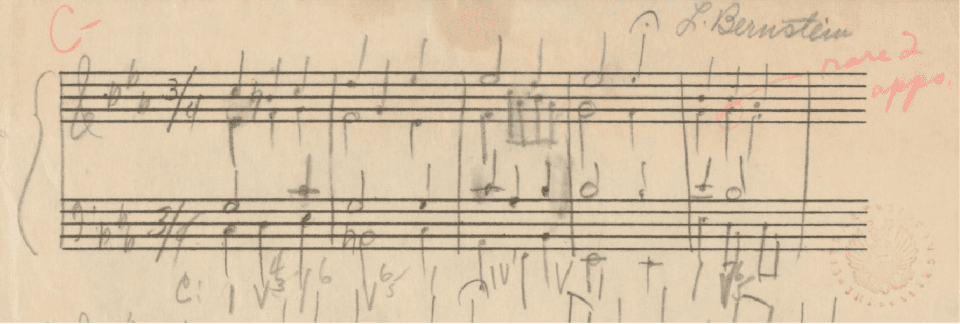

I couldn’t figure out how to get the sounds I heard into my head onto the paper. Worse—I wasn’t even sure if I should put those sounds to paper.

So I became an editor.

Or rather, I added the editing minor to my undergrad degree.

And it was the best choice I ever made for my music.

At the time, the main professors in BYU’s editing minor were Mel Thorne and Marvin Gardner. Now retired, both men even at that time belonged to a group I affectionately considered ”The Greatest Grandpas of Utah Valley.”

Mel’s background was in academic and book publishing. He was more down-to-earth and task-oriented.

Marvin’s background was in magazine publishing. He was more effusive and gentle.

Both were consummate professionals and unflaggingly generous in the mentorship they gave to their students.

After multiple classes from both professors and an internship with Mel, I came away with a transformed view of writing and editing.

Up until that point, like most of us, I dreaded getting my English papers back drenched in red from all the corrections teachers would put on them.

I associated writing with “being graded” and editing with “the person doing the grading.”

Mel and Marvin utterly transformed how I understood this relationship.

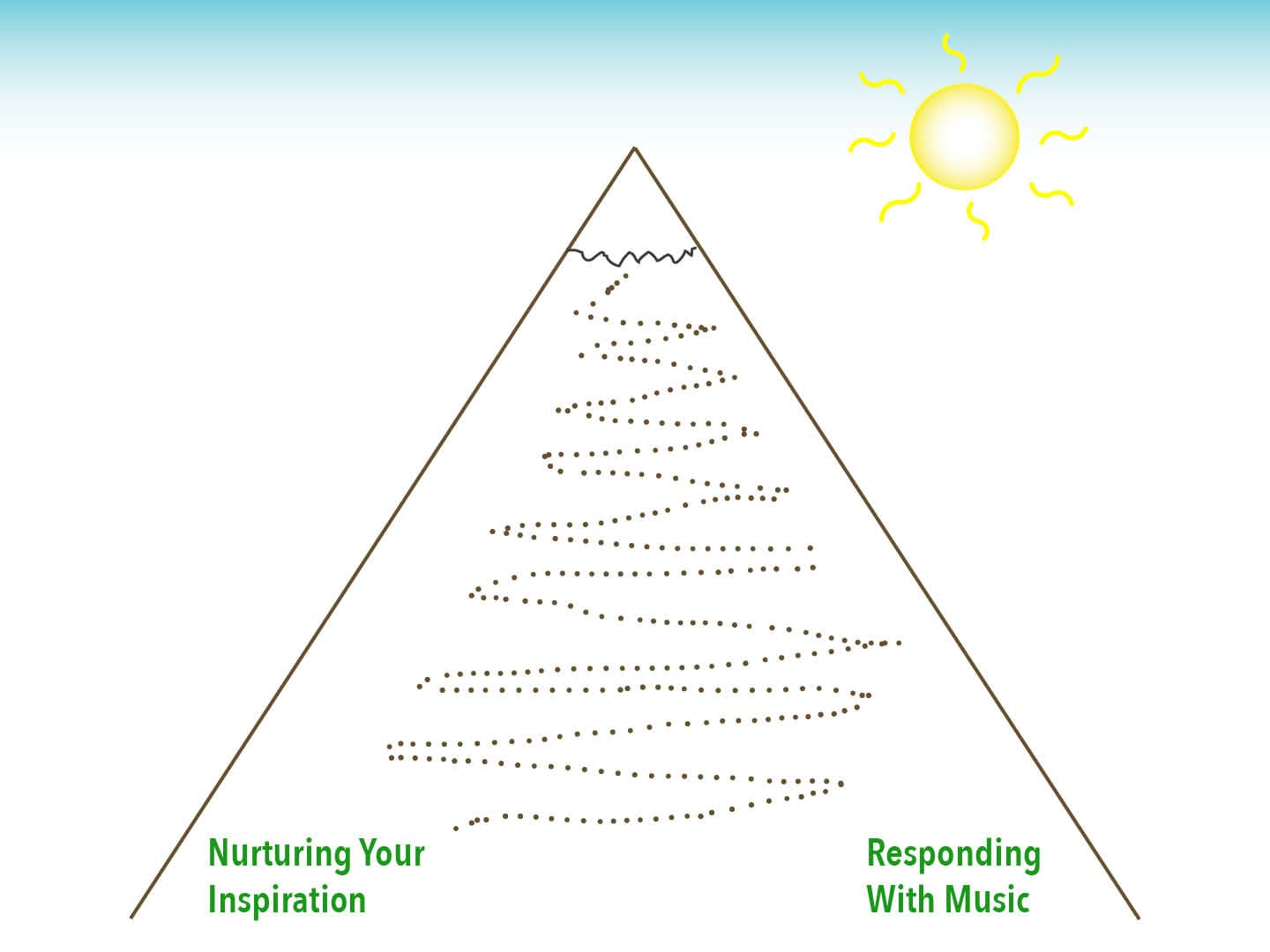

They showed me that, in the professional world, editors and writers are allies, not adversaries. The goal is for the team to complete the task well and efficiently—not any one individual.

Writers who insist on polishing their writing to perfection before sharing don’t just waste everyone’s time, they act defensively in bad faith.

The whole purpose of having an editor is so that the writer doesn’t have to get everything right at first. The editor-writer team can produce better prose faster when they work together than when the writer tries to make everything perfect first.

When I understood that my job as a writer was simply to get my ideas on the page, not to perfect them, that liberated me.

Even if I hadn’t fully articulated my ideas. Even if I couldn’t yet fully understand them. I knew, “The editor will help me fix this!” (Editors are a lot like therapists, helping you articulate the things you feel but don’t yet understand.)

I saw that my job was simply to give the editor something to work with.

This point was hammered home last week during office hours in the Wizarding School for Composers.

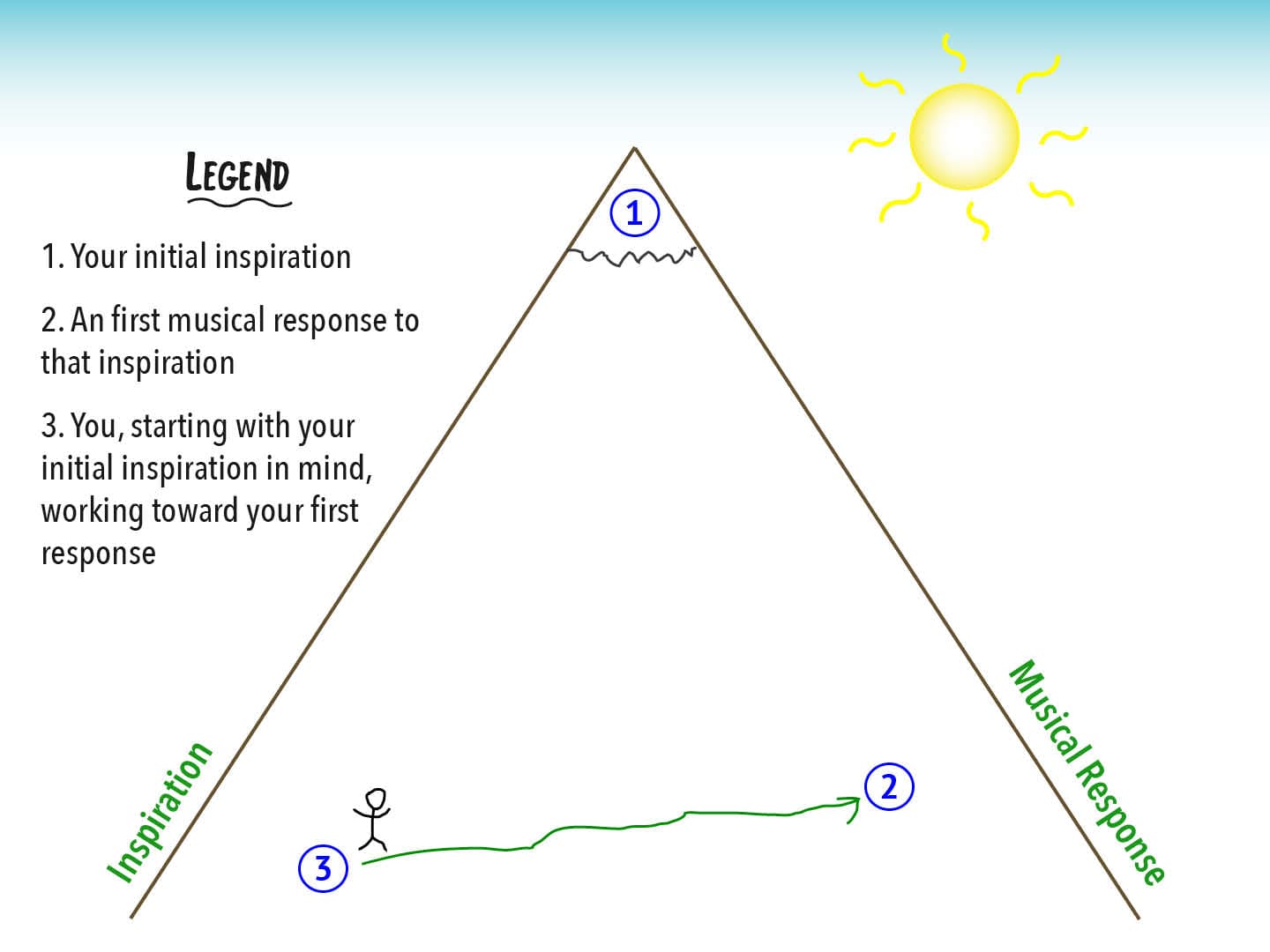

One of my students, Joseph Fletcher, shared the “two rules of creativity” he had come to understand from our work this semester:

- “Don’t be afraid of a half-baked idea.”

- “Don’t settle for the half-baked idea.”

Rule One describes the writer’s role. Rule Two describes the editor’s.

As creatives, we often struggle with accepting the validity of both roles.

In Joseph’s case, he explained, “I think I’ve been in Rule Two for a long time, but I haven’t been very good at Rule One. I just mull and mull, so my progress is slow. My willingness to just throw something at the page and then start iterating from there—that’s the thing in my process I’m hoping to adapt.”

Many others have the opposite problem: They’ll gladly generate and generate, but when it comes time to refine their ideas, they struggle.

But knowing that these two roles exist and can work in harmony is half the battle.

It didn’t just make writing prose easier and more joyful for me, it did the same for my music. And it can do the same for yours.

Which role, editor or writer, do you relate to more?

(Photo: Nic McPhee/Flickr)