As I explained in my last post, when you say “I can’t write music today,” you’re probably not referring to an ability, but to an outcome or aspiration.

And you’re probably correct. As BJ Fogg explains, “you can only achieve aspirations and outcomes over time if you execute the right specific behaviors.”

So, you probably can’t compose today if by “compose” you mean something like:

- “Write impressive, innovative music like taking dictation.”

- Or “Wait to get started until I have the right ideas.”

- Or “Complete and polish an entire passage—not just a few bars, let alone only one aspect of it.”

On most days, such aspirations are totally unrealistic even if your name is Miles Davis or Augusta Read Thomas.

This is why the key tool I teach in the Wizarding School for Composers is “Shrink the Frame.”

As a baseline, “Shrink the Frame” means

“Give yourself tasks you actually have a hope of accomplishing.”

More optimistically, it means

“Break composing down into tasks that are short, clear, and even fun.”

Or, in other words,

“Identify, practice, and celebrate the behaviors that lead to your desired outcomes and aspirations.”

But what would that look like on any given Tuesday? And how could it possibly help you achieve even your highest artistic aspirations?

How Do You Climb a Mountain?

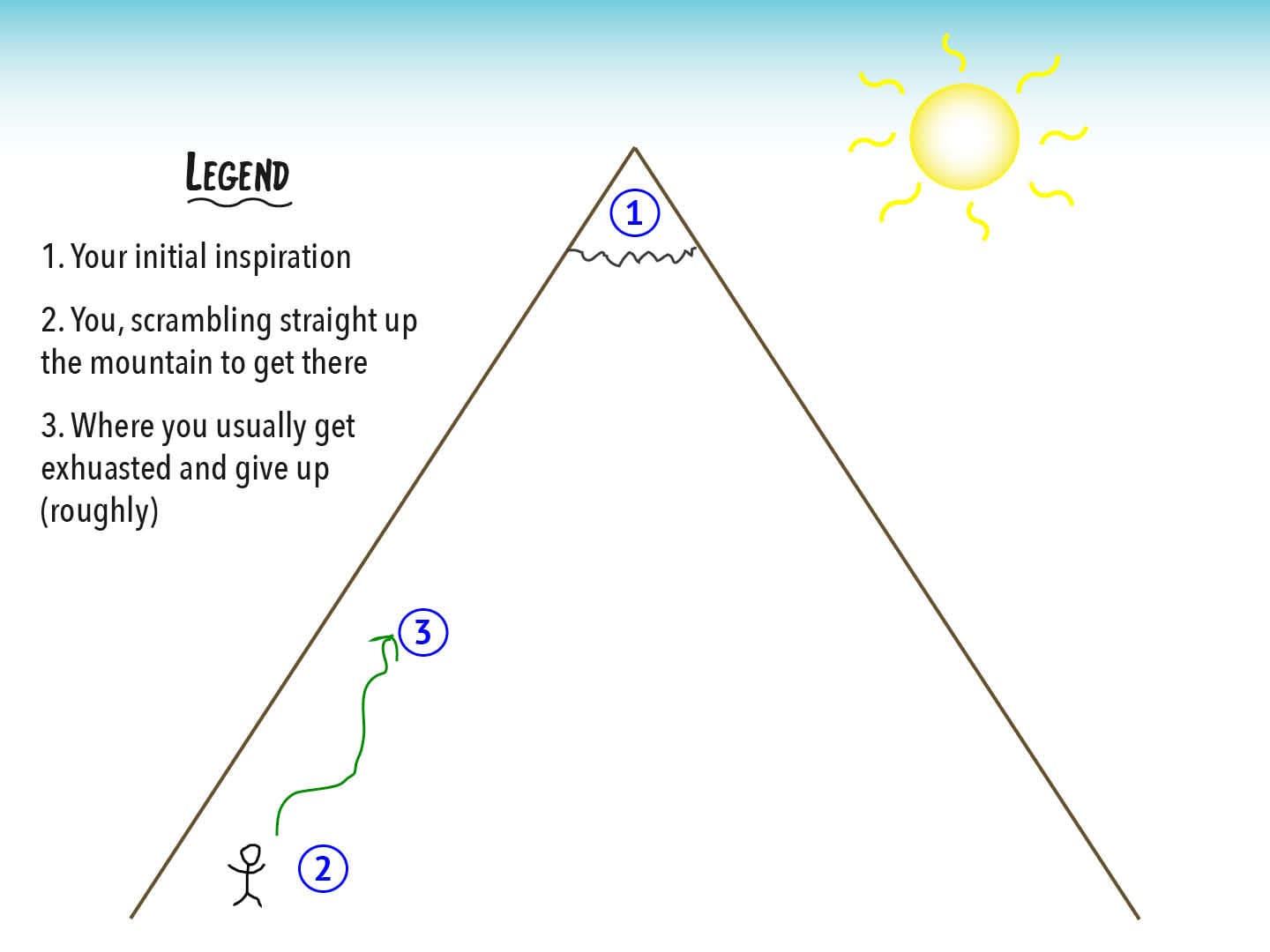

Imagine yourself about to climb a mountain. (I’m sure composing has felt like this for you at some point.)

Picture yourself standing there at the base, needing to figure out the fastest way up.

The first, tempting idea is to scramble straight up the face of the mountain. . . .

Anyone who’s hiked a mountain knows this is a dumb idea. You’d be exhausted before you made it even a third of the way up.

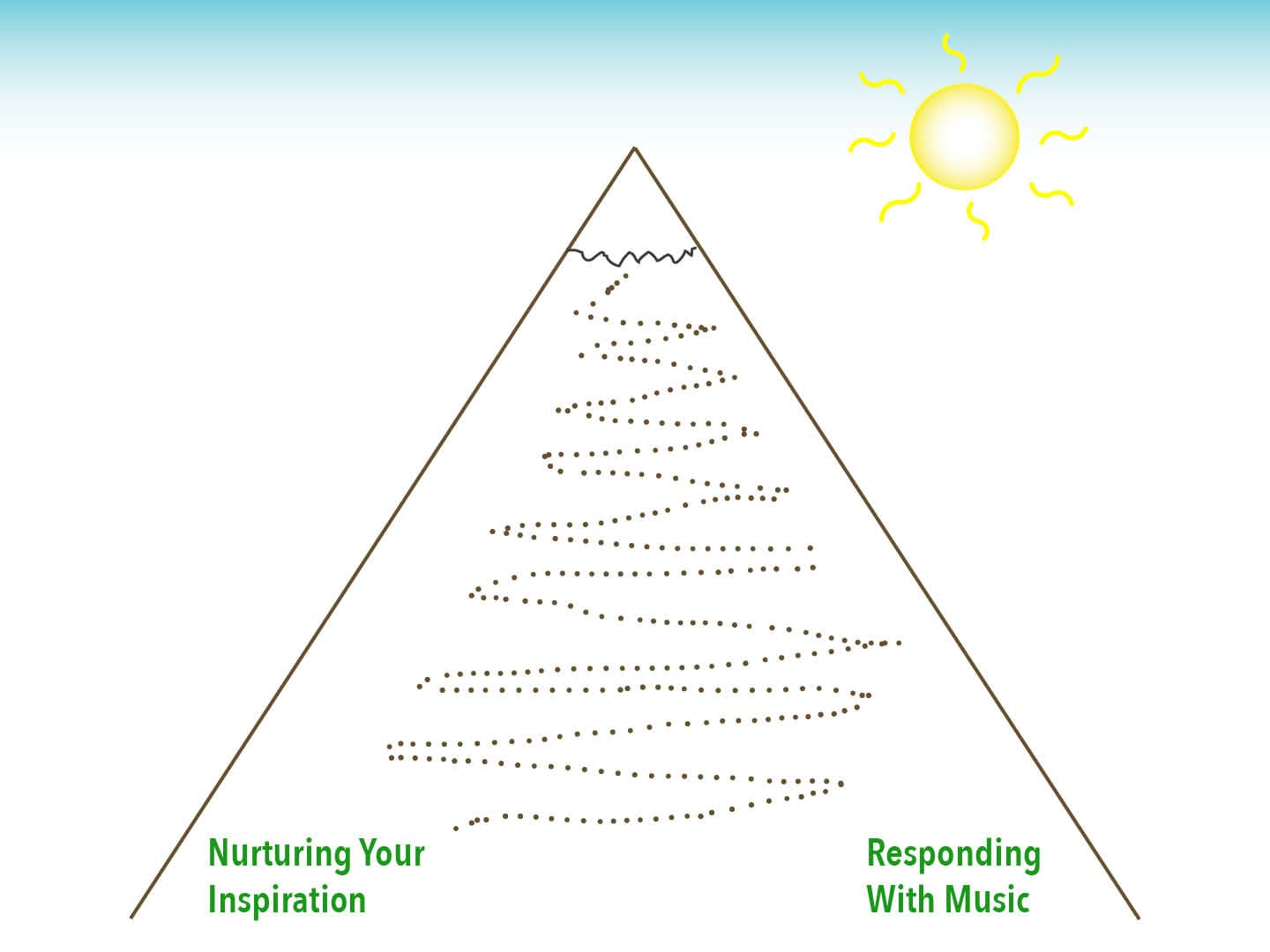

Instead, you look around for the trail and notice it consists of switchbacks, all the way up. Sure, this will still take effort. (After all, it’s still a mountain.) But you know you will have the energy and inspiration to keep going if you take this route instead.

So, wisely, you decide to take the switchback route.

The Scramble

Too often, that same wisdom does not carry over into composing.

At the start of each new piece, we typically catch some vision of what the completed work could be. That initial inspiration could be:

- A song, piece, poem, novel, TV show, film, ballet, etc.

- A story, experience, relationship, or memory

- A musical fragment or something nonmusical

- Even something as simple as a feeling or an intuition

Then, whatever the source, while that vision is still hazy but intoxicating, we attempt a mad scramble toward its summit.

This process hardly ever works. Its results are as predictable as they are unfortunate:

- Your initial attempts do not get you anywhere close to completing the piece or capturing your vision.

- Unable to move forward, your enthusiasm evaporates, and you end up in an emotional puddle.

- You procrastinate until pressed against a hard deadline—then turn your life upside down as you rush to finish.

- You learn to associate composing with anxiety, pressure, and massive expectations—making composing something you want to avoid.

- You internalize the mantra “I work best under pressure,” though you secretly know this is just an excuse for your ineffective work habits.

Your ineffective work habits are not a moral failing. They are not a taint on your character.

But the truth is, you don’t work best under pressure. No one does.

There is a better way, and you can learn it.

The Switchbacks: Your Initial Musical Response

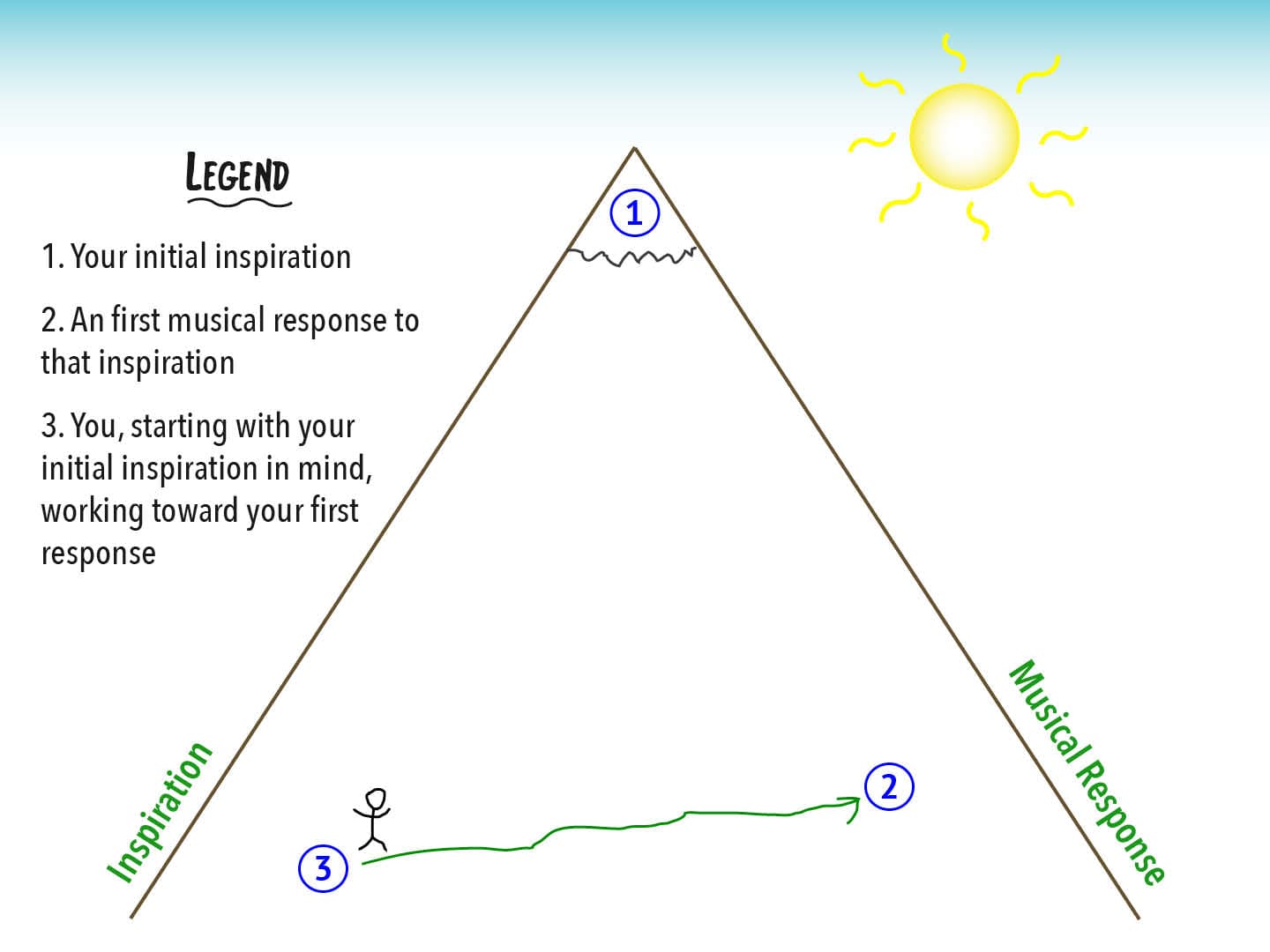

Let’s go back to the start. You’ve just caught some vision of what the completed work could be. How can “switchbacking” help you proceed with a sense of ease—and even fun?

Imagine the two sides of the switchback represent two broad categories of action:

- Nurturing your inspiration

- Responding with music

Casting aside debilitating stories about the creative process, you don’t fixate on one big (but hazy) inspiration and make one massive push to get there.

Instead, you

- Capture that initial inspiration in words, pictures, recordings, whatever.

- Create a small, initial musical response to your inspiration.

This response could entail you recording 3-5, minute-long improvisations. Or finding 12 chords that remind you of the inspiration. Or choosing which instruments would best capture its sound. etc.

Each one of these possible responses represent a single compositional task. You get credit for doing any and every one of them. All your work counts, even if it no one can see or hear it in the finished product.

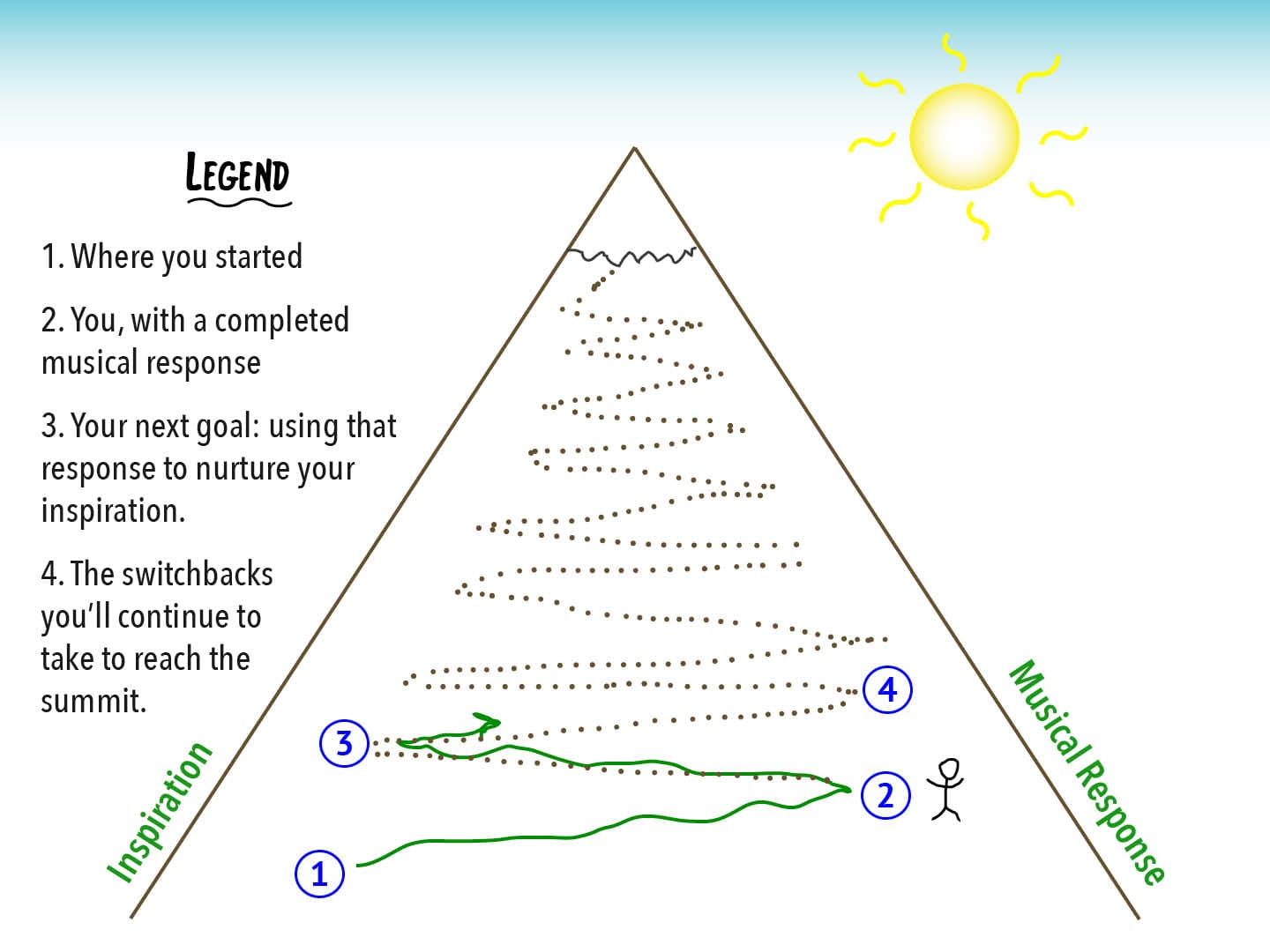

The Switchbacks: Nurturing Your Inspiration

There will come a point, however, when your initial inspiration runs out of steam.

This is not a threat.

You don’t need to fight it, flee it, or freeze (for instance, respectively: beat yourself up, go do the dishes/watch Netflix, or start taking quick, shallow breaths as you tighten all your muscles).

No, you are perfectly safe and just fine—you’ve simply come to the end of a switchback.

So now you simply need to start moving the other direction: use the music you’ve created to further nurture and refine your inspiration.

Go back to your notes or diagrams, and ask yourself:

- Of the musical fragments I created, which best capture my initial inspiration? Why?

- In what ways do these resonant fragments I created affirm my initial inspiration?

- In what ways does it change or deepen that initial understanding?

- How does it broaden that understanding? Of what other songs, poems, images, experiences, TV shows, sensations, relationships, etc. do these resonant fragments remind me?

Answering these questions will give you new musical ideas.

In turn, these new ideas will help you future refine and nurture your inspiration, which will lead to richer musical ideas . . .

And thus will the whole cycle continue. All the way up the mountain, you will keep switching back and forth between musical ideas and extramusical inspirations until, one day, you reach the summit.

Though the whole process can take days or even months, at no point is it onerous, because you always had one next, small step you could take.

Go Try This at Home!

If you’ve been avoiding your work or if you’re an entrenched procrastinator, you might not believe me. So go try it.

- If you’re stuck on a particular musical passage,

- Pretend you are an audience member and interpret what you’ve written with your imaginative and associative mind.

- Nurture your inspiration with the questions above and watch that process inspire new musical ideas.

- And if have been sitting on an inspiration, but haven’t been sure how to express it, you’re in luck—because you’re about it have a ton of fun.

- Choose a musical behavior you can do in 20 minutes and just. start. playing.

- Use your inspiration as a prompt for that musical game—whether it’s writing variations on a melody, designing new sounds in your DAW, whatever.

- At the end of 20 minutes, check back in with your inspiration, see what resonates, and keep refining.

On whichever side of the switchback you begin, continue the process of iterating both your inspirations and your musical responses.

Soon enough, you will find yourself on the top of your creative mountain, not only having a completed piece, but also having thoroughly enjoyed the hike.

As Hans Zimmer says,

“Writing music [can] be something you indulge in, like a delicious meal, an intimate conversation with your best friend or an endless day at the beach. Something you don’t want to hurry, something you don’t want to end.”