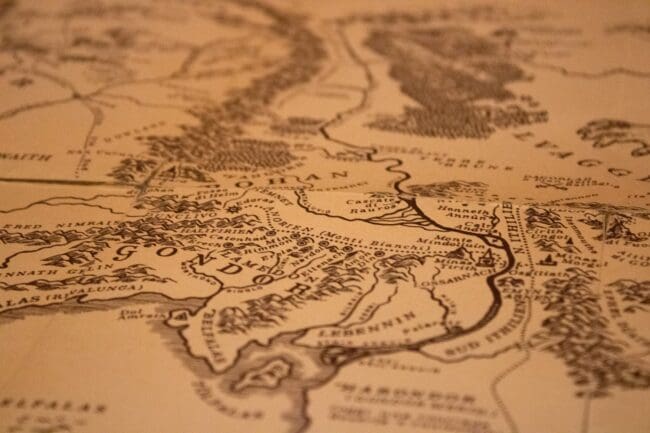

Among fantasy stories, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is renowned for the depth of its world building.

Just to write the trilogy, Tolkien created extensive backstories, poems, maps, and even entire languages, including their calligraphies.

Tolkien’s world is so thorough that, even when he doesn’t share the backstory in a given passage, it still feels vivid and three-dimensional. More than just telling you that his world is magical, Tolkien conjures the feeling of magic through his stories’ rich details.

Such world building is the bread and butter of a modern musical education, too.

In conservatories and universities, all musicians learn:

- More than a dozen scales and modes

- Scores of chord qualities and pitch set classes

- All the rules of and exceptions to common-practice voice leading

- A smorgasbord of twentieth-century techniques

- The historical backstory behind all these sounds

Many also learn:

- The intricacies of writing counterpoint in the styles of Bach and Palestrina

- The standard and extended techniques of all the orchestral instruments and, often, the pop and jazz ones, too

- The ins-and-outs of electronic music recording and production

All of these sounds and techniques are the equivalent of Tolkien’s world building. They introduce students to not just one, but multiple different musical worlds.

Musicians call these different musical worlds “styles,” “genres,” or “topics.” Composition programs even teach musicians how to create new styles and proselytize the idea that such original world-building is essential to being a “good composer.”

All this should be enough to help students become confident composers, right?

Sadly, no.

For all this world-building knowledge, most musicians trained this way never become composers, and the few who do still struggle to feel like they can conjure musical magic at will.

At best, they often feel like imposters, and, at worst, they feel sheepishly impotent.

Why isn’t mastering the rules of 16th century counterpoint or the intricacies of clarinet multiphonics enough to create great music?

Because that’s like trying to conjure magic using only earth, when real magicians use all four elements: earth, air, water, and fire.

Tolkien didn’t just create a world (earth): He had a story to tell (air), inspired by deeply personal influences (fire) and channeled through effective creative processes (water).

So, yes, world building is essential. It is as key an ingredient in Tolkien’s success as a writer as it is yours as a composer.

But without the other three elements, world building is too often dead on arrival.

Don’t Miss Next Week’s Post

Sign up to stay in the loop about my music—and ideas for your own composing!