Every orchestration textbook will tell you that the lower limit of the violin (scordatura aside), is a G3 (G below middle C).

But even with a normally tuned violin, composers don’t always obey that limit. Here are two examples (plus a bonus one in viola) that show why a composer might write beyond that written limit.

To Preserve a Melodic Line

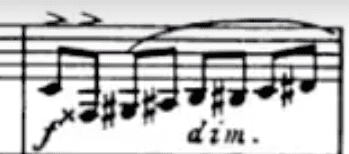

In Richard Strauss’s Sinfonia Domestica he writes (at reh. 74) this:

As Ernest Toch points out in The Shaping Forces of Music, “It is the pitch-line, its curve or curves, its shape, its profile, its ascensions and descensions which determine the character, the gesture of the melody. . . . Richard Strauss, in his ‘Sinfonia domestica’, draws the last consequence of this consideration by entrusting the violins with a note which is even below the range of the instrument and therefore cannot be produced. The passage is reinforced by the violas and horns and its sounding is thus assured. It would be intolerable, even to the composer’s eye to replace the low f# with its higher octave. He wants the line at least to be understood — playable or not” (67).

If I were writing that passage today, I might parenthesize the note to make it clear to the players that I don’t expect them to play it. Regardless, this is a valid, albeit rare, reason to write below the range of an instrument.

To Preserve the Tonal Meaning

A far more common reason to write below the written limit is to clarify the tonal meaning of a pitch. In this case, composers aren’t actually writing an unplayable note; they’re simply spelling it in an unusual manner.

For example, in the first movement of Borodin’s String Quartet no. 2 (bar 55), Borodin writes:

Likewise, in the second movement of his Serenade for Strings, Dvorak writes a low B for the viola (bar 4):

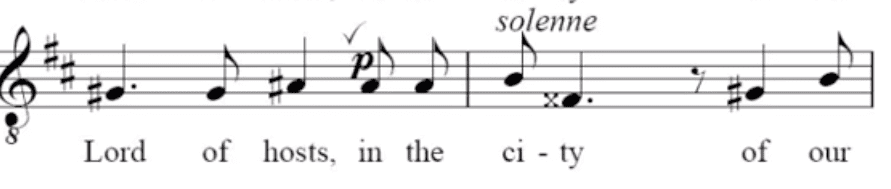

In both cases, the composer is harnessing the notation to tell the performers something about the pitch relationships. Just last week, a fellow evensong choir member of mine identified a similar case in this tenor line in Elgar’s “Great is the Lord”:

“Why did Elgar just not write this as a G?” he asked.

In each of these three cases, the composers wanted the performers to know that these pitches did not have a chromatic relationship, but rather a diatonic one. In other words, they wanted the performers to know that the note they were playing (or singing) was acting as a leading tone to the note that followed it. In an earlier blog post, I referred to this as “structural chromaticism”: “these notes merely represent the overthrow of one diatonic collection (say, CDEFGAB) by a different diatonic collection (say, C#DEF#GAB).”

In the examples above, Borodin and Elgar both write F-double sharp to tonicize G-sharp, and Dvorak writes B-sharp to tonicize C-sharp. Now, you may note that, whereas C-sharp minor is the key of Dvorak’s entire phrase, neither Elgar or Borodin ever establish a key of G-sharp. That difference is immaterial. In tonal music, pitch functions can last as briefly as a single interval. The entire scale never has to be present, nor must the music match the prevailing key signature.

So if these tonicizations are so brief, why do these composers write them with these “strange” spellings? Why write a low F-double sharp for violin or a low B-sharp for viola? Simply put, because the diatonic spelling helps performers understand the musical meaning better than the chromatic one. In each of these three cases, the “simpler” chromatic spelling (G to G-sharp or C to C-sharp) would obscure the diatonic relationships that Borodin, Dvorak, and Elgar want us to hear.

Don’t Miss Next Week’s Post

Sign up to stay in the loop about my music—and ideas for your own composing!