I love the opening swirl of violins in “Jupiter” from Gustav Holst’s The Planets. Who doesn’t?

Take a moment and listen to it:

It’s thrilling!

But what really gets me going as a composer are the details of its composition. This passage is extraordinarily elegant.

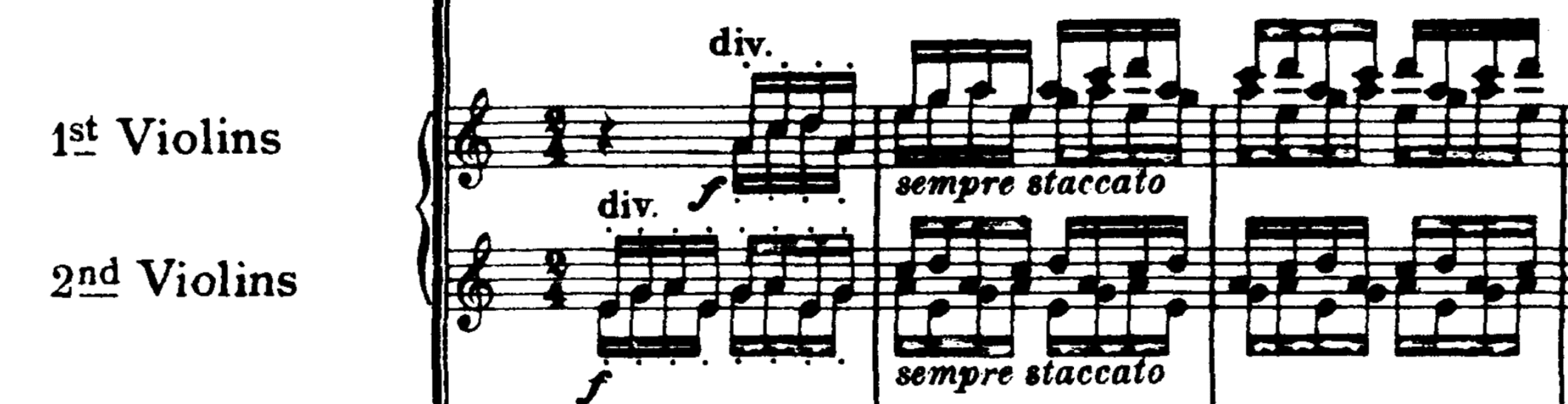

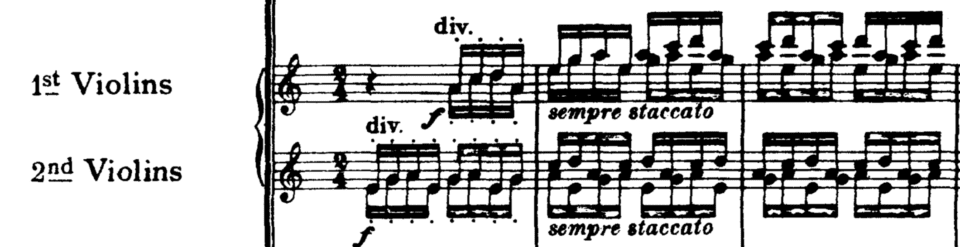

Here’s the excerpt from the score:

What makes this passage so elegant?

- Motive: The texture is composed of a single, three-note motive: a minor third followed by a major second. Holst presents this motive in two transpositions (starting on E and A) in two octaves (E4/A4 and E5/A5). Elegance is how the passage is composed of such a limited set of materials.

- Disposition: Though we hear the first two bars as a two-octave, upward run, it’s actually Holst introducing each transposition separately. The fact that the motive spans only a fourth makes it extraordinarily easy to play on the violin. Elegance is how Holst distributes the pitches in this easy-to-play manner to generate a larger effect.

- Rhythm vs. Meter (I): Holst casts his three-sixteenth-note motive into four-sixteenth-note beats. Each entrance initially seems like a four-sixteenth-note motive, but the ensuing music dispels that notion. Instead, we soon hear that Holst has set up a 4 against 3 polyrhythm. That is, the rhythmic placement of the motive relative to the meter keeps shifting in a 4:3 ratio. Elegance is how this simple tension creates excitement and energy.

- Rhythm vs. Meter (II): Though the motivic relationship to the meter forms a kind of polyrhythm, the rhythmic relationship of each transposition relative to the others remains constant. For instance, the E4 transposition always sounds A-E-G while the E5 transposition sounds E-G-A. Because each instance of the motive is the same 3 sixteenth-notes long, this 1:1 duration ratio ensures that they remain in the same micro-canonic relationship with each other. Elegance is how Holst composes the texture canonically rather than micromanaging the details.

- Orchestration: Coupling instruments in octaves is one of the foundations of common-practice orchestration. Holst does it constantly in The Planets. This passage can also be read as a kind of octave doubling: the canon with entrances on E and A in bar 1 is repeated an octave above in bar 2. The resulting texture’s polyrhythmic and pentatonic wash reinforce the impression that this relationship is an octave doubling of two lines rather than Holst wanting you to hear the four individual lines. The rocking strings that open Thomas Adès’s Tevot fill a similar purpose. As individual lines, they have direction, but as a composite texture, they create a grainy wash rather than discernible counterpoint. Elegance is taking a simple, common idea and presenting it in a fresh, becoming way.

As a composer, I love such elegance in other’s music and I strive for in my own. These kinds of musical ideas captivate me, because they create the kind of shimmering, ambiguous tension like light through a gemstone or waves reflected on the bottom of a pool. They represent one kind of musical depth: patterns whose components can be heard but which do not resolve into an unambiguous impression. The tension that remains creates a space where the soul can live.