Whether you’re just starting out at composing or have been writing music for decades, improving your composing skills can help you find greater technical mastery, artistic fulfillment, and career success.

Deliberately developing your composing skills is especially important if you’re not yet as good of a composer as you hope to be (which describes most of us composers).

That said, the “best” way to get better at composing depends on what you're trying to improve.

Here are five suggestions:

1. Mastering Specific Techniques

Specific techniques are most easily practiced in isolation. This is why universities teach specific courses on harmony, ear training, counterpoint, orchestration, film scoring, etc.

If you want to learn the full suite of standard compositional skills, a university degree is a good option — but it’s not the only one.

Nowadays, you can also learn any of these topics from online courses and teachers, both paid and free. So, for instance, if you feel fine with your counterpoint chops, but what to deepen your orchestration skills, you can, say, follow Thomas Goss at Orchestration Online or study IU’s Instrumental Studies for Eyes and Ears.

That said, composing cannot be reduced to isolated techniques. The next level of mastery is understanding how these techniques work together.

2. Mastering Existing Styles or Creating Your Own

Style is the most basic way that musical elements work together. Simply put, musical style is the specific combination of characteristic timbres, rhythms, harmonies, textures, and forms that give a piece its unique sound.

Whether you want to write in existing styles or to create your own, here are four good options for learning style:

- Copy scores or transcribe recordings. At its best, these practices force you to notice all the little details in a piece. However, if you copy scores mechanically, you’ll mostly just improve your notation software or penmanship skills without learning much about the music itself. Likewise, transcribing works best when you slowly increase the difficulty to match your ability.

- Score study. Without copy scores or transcribing recordings, you can still learn a lot by simply studying the score. Although solid theory chops greatly help, you don’t need a theory PhD to do this. You just need keep an eye out for patterns and trends.

- Writing pastiches. One of the best ways to learn a particular style is to try writing in it. Take the elements you learned from score study and replicate them using your own pitches/rhythms. Mastering pre-existing styles is one path to developing one’s own style.

- Experimenting with unusual materials. This is the route most commonly found in university composition courses. Working with unusual sounds gets you out of our comfort zone and forces you to imagine possibilities you otherwise wouldn't have.

Many composers develop their own style using combination of these strategies—but remember that developing your “artistic voice” is bigger than musical style.

3. Creating Meaningful Forms and “Magical” Moments

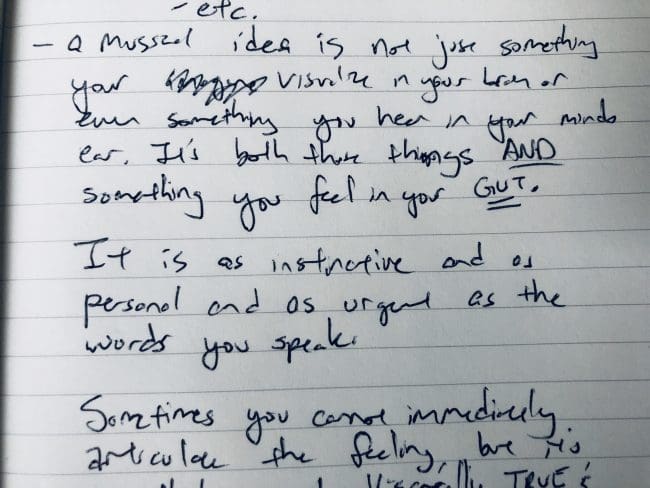

The chord that gives you goosebumps, an ostinato that rivets you to your seat, the tune that gets stuck in your head — moments like these are why we’re all here. We hope to experience something magical.

Music cognition research has shown that this “musical magic” is NOT a product of style. Having a “signature sound” does little to help you create these effects. Rather, musical magic happens through repetition, tension, and surprise.

As with studying style, learning how to creating meaningful forms and magical moments requires you to study how the elements of music work in coordination.

For this, score study and analysis are a MUST. However, rather than labelling features (as in stylistic analysis), in analyzing musical magic one must focus on relationships and timing.

Though some insightful teachers and courses explain these elements in ad hoc ways, the Wizarding School for Composers is the only composition course that systematically shows the compositional processes required to create musical magic.

4. Streamlining Your Creative Process

Up to this point, we’ve been talking about ways to improve your craft. Though craft ensures you can express yourself freely, it’s the larger creative process that ensures you have something meaningful to say.

Many composers' creative processes are woefully underdeveloped, so they procrastinate and are self-critical — but that doesn't have to be you.

The creative process has specific steps and procedures you can learn. Read Nico Muhly's “Diary” essay from the London Review of Books, Twyla Tharp's The Creative Habit, or David Usher's Let the Elephants Run for ideas.

Your goal is to create "workflows": replicable procedures that enable you to reliably accomplish specific musical tasks.

"Composing" is not a specific task any more than (say) “farming” or “house building” is. "Write an 8-bar melody in the style of George Gershwin" is.

5. Improving at Self-Evaluation

The tips I listed above are essential to developing a mature ability to self-evaluate. As you improve on them, you will likewise grow in confidence about your musical and artistic judgment.

Until you've developed that ability, get a teacher. They'll be able to help you understand how all these pieces fit together in a way that you cannot until you've mastered them (which takes at least a decade).

Third, even after you've mastered them, seek feedback, and even lessons, from your peers. Composers tend to be bad about this. They think that they can or should work in isolation. The truth is that humans are social creatures, and whether is bread baking, athletics, or composing, we improve best in collaboration with each other.

Your Next Steps

Now that you've read the list, what should you do? Here are two good ways of knowing:

- Ask a teacher or peer who knows you and your music

- Follow your gut

I'm guessing (/hoping) you already have ideas — follow those.

I’m also happy to meet with composers (for free!) to talk about their music and goals and identify what next steps they can take. Feel free to schedule a call with me.

Last but not least, I'd love to hear your take:

- Did I miss anything on this list?

- What else would you have added?

- What other questions do it leave?