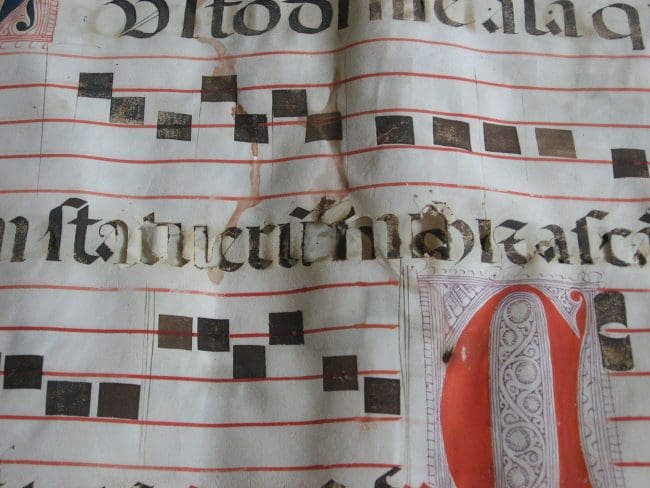

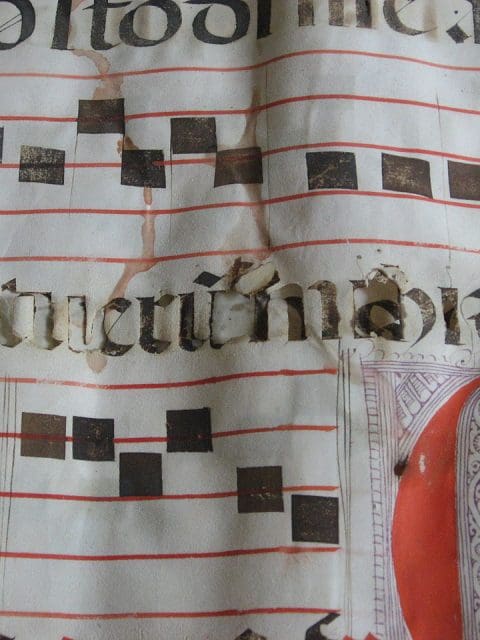

“Inherent vice,” says Wikipedia, “is the tendency in physical objects to deteriorate because of the fundamental instability of the components of which they are made, as opposed to deterioration caused by external forces.”

As a property of physical objects, this is why certain papers and films last longer than others. It also is why materials deteriorate the way they do.

But what interests me about inherent vice are its potential musical analogies. Here a few examples of how inherent vice can be recreated in music.

Fred Rzewski: Les Moutons de Panurge

Rzewski makes it easy for performers to get lost, and in the score, he explicitly directs the performers that “if you get lost, stay lost. Do not try to find your way back into the fold.” The analogy to inherent vice is pretty clear: the piece will fall apart. What’s fascinating though is how Rzewski repurposes this as a virtue. Thus, the title feels to me like a humorous reference to Isaiah 53:6: “All we like sheep have gone astray.” (To my ears, there is no obvious reference to Handel’s setting in Rzewski’s piece, other than a general, wandering melodic contour.)

Alvin Lucier: I Am Sitting in a Room

As with Rzewski’s piece, the inherent vice of Lucier’s musical-acoustic scenario is the desired outcome. Here, the vice comes not from confusing the musicians, but from harnessing the result of rerecording the same speech, repeatedly, which gradually washes out the speakers voice and reveals the acoustic resonance of the room in which it is performed. The overall process and result feels like a metaphor for merging with the universe and reminds me of the Buddhist doctrine of anattā.

Michael Gordon: Gotham, Part III

The third part of Michael Gordon’s Gotham undergoes a similar process, albeit composed out and for orchestra. I find fascinating the different textures that he teases out of having the violins initial line unravel. Inasmuch as the process is composed out, rather than a result of the score’s execution, I wouldn’t consider the vice here to be as “inherent” as Rzewski’s or Lucier’s pieces. It’s more like “predestinated vice”: the composer decided the piece would gradually fall apart, so he ensured that it happens.