As musicians, we learn a lot of technique in school. It’s what we’re graded on. It’s often what we value in others or ourselves. It can be easy to think that technique is the be-all, end-all.

At the very least, focusing on technique feels comfortable. It’s what we’re used to. It feels like something we can control.

But once we graduate to larger world—unless we’re one of the few who land the full-time orchestral gig or university teaching job—the reality is starkly different.

Professional careers require more than flawless technique. These demands can feel daunting to even the most talented and proficient musician:

- How to find gigs and secure commissions

- How to cultivate an audience for our work

- How to create and execute projects that fulfill our artistic dreams and impact out communities

- How to negotiate money and contract issues

- . . . and on and on

These are difficult problems.

Because of our training, our first instinct is often, “Let me throw more technique at these problems. That will get me the success I want!”

Yet—hopefully sooner rather than later—we discover that, for these questions, technique is often a cop out:

- An excuse not to show up by saying “I’m not ready.”

- A defensive reaction when the audiences we inherit aren’t interested in our work: “They just don’t know quality when they hear it.”

- A hurdle that maintains gatekeepers’ power by encouraging us to say, “I must not be good enough yet.”

Insecurity, cynicism, powerlessness—these are some heavy feelings.

But they are not the truth of your career or potential.

Your career is not constrained because you lack the technical mastery of Yo-Yo Ma or Augusta Read Thomas.

You can create the artistically fulfilling, socially satisfying, and financially rewarding career of your dreams—if you widen the scope of your artistic possibilities past technique.

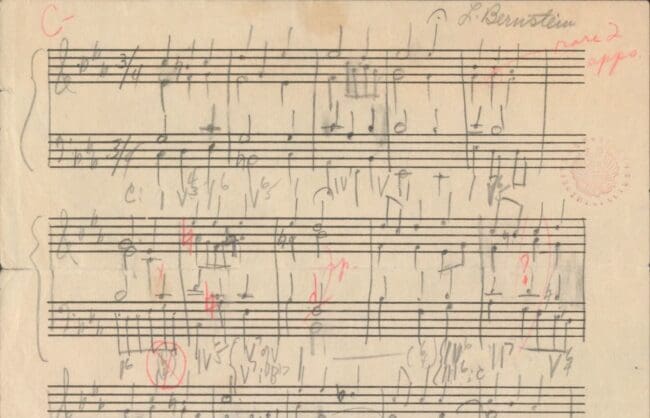

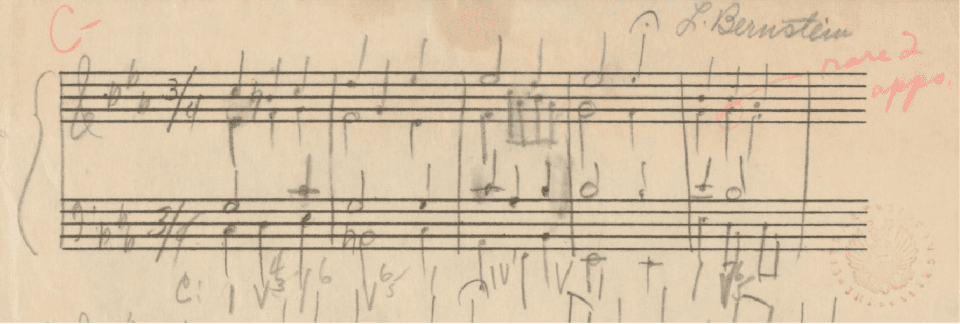

The image that started this post comes from the harmony assignments that Leonard Bernstein wrote while a student at Harvard . . .

He got a C-. But I don’t have to tell you who Leonard Bernstein is or what he did.

Just like Lenny, there’s more to your career than how good certain gatekeepers say your technique is—even if your technique has room for growth.

So if technique is only part, what does a complete musician look like?

The answer is what I call your Artistic Voice.

And I’ll be sharing more about it in the coming weeks . . .