With COVID-19 sweeping the world, many of you many have joined me where I’ve been in for the past three years: working from home. As everyone is discovering, it’s tough.

Here are five tips I can offer from my experience as grad student and freelancer.

1: Log Your Hours

The temptation of having a fully flexible calendar is for you or others to equate “flexibility” with “endless free time.” You must work to disabuse yourself and others of this idea. Make and keep appointments with yourself.

Get a time-tracking app (or use a consistent notebook or spreadsheet) and log your billable hours (exclude bathroom trips, meals, non–work-related email and internet, etc.).

Logging billable hours is more useful than tracking your overall start and stop times, because it gives you a better indication of how much you’re actually working in a day. Everyone already knows that an “8-hour work day” doesn’t mean you’re working for a solid 8 hours. In practice, once you factor in the coffee and bathroom breaks, the unavoidable interruptions, the pointless meetings, and so on, an “8-hour work day” represents about 6 billable hours.

So when you’re working from home, shoot for that number. It should get you about where you need to be in terms of daily output.

2: Set a Morning Start Time and Don’t Sleep In

The most important appointment you set with yourself is the one first thing in the morning. If you don’t log at least a couple billable hours in the morning, it’s nearly impossible to log 6 billable hours by the evening.

Whether it’s an early bird hour (6 AM? 5 AM?) or a more night-owl friendly one (say, 9 or 10 AM), be sure to log at least one hour in the morning. You’ll thank yourself by the evening.

3: Take Your Downtime Seriously

The second most important appointment you set with yourself is in the evening. When you work from home, it can be tempting to just keep going. For your health and sanity, do not do that. Once you’ve reached whatever billable hour goal you set for the day, you are free. Go take care of yourself: exercise, read a book, spend time with a loved one.

When working from home, it is crucial that you respect your human needs for food, exercise, sleep, and play. Otherwise, working from home quickly becomes unsustainable.

When I was working on my dissertation, I often had very little social time. I felt lucky if I could get in 2 social events per week. Despite that, it was some of the happiest months of my life, because I was otherwise taking care of myself. I had a routine that ensured I was well-fed, exercised, and had sufficient sleep.

Be sure to do the same for yourself.

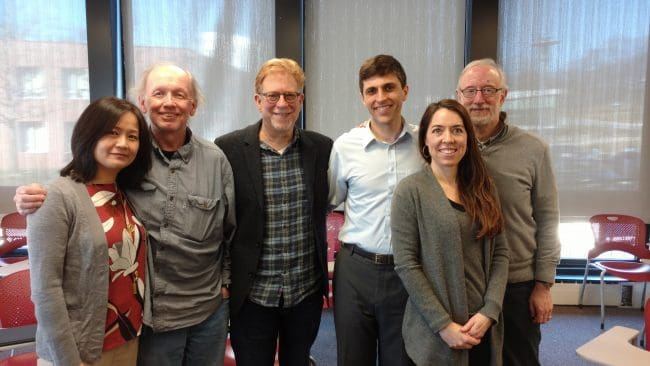

4: Schedule Time to Talk with Colleagues

One of the benefits of working at an office or at a school is that you are surrounded by colleagues. They act as sounding boards and positive social peer pressure (“Hannah’s working right now, so I should be, too”). Even a five-minute chat about the latest TV episode or your friend’s weekend plans can work wonders for your productivity.

When you work from home or even a library or coffee shop, you miss these social benefits.

So schedule it in. Make appointments with your friends to meet up during the week. Call or FaceTime with them (better than texting because it has a clear start and finish).

Their input will increase your output.

5: Let Life Happen

You will have sick days and stuck days and surprise errand days. The goal isn’t to make a schedule and stick to it perfectly. So when life happens, embrace it and move forward:

- Can’t log 6 billable hours today? Instead try for 4 or 2 or even 15 minutes. All progress counts and keeps the momentum going for days when the wind is at your back.

- Feeling overwhelmed? Let yourself take a few mental health hours or even days. Do tasks that have a clear start and end.

- Feeling stuck in loop? Do you feel the pull to waste time? Give that urge your attention, name it, and let it go. Stand up and walk around a little. At least, stare away from your computer screen and do some breathing meditation for a minute or two.

Conclusion: Learn Your Process

These suggestions represent what has worked well for me. Use them merely as a starting point. At the end of each work day, take a few minutes to reflect on what worked well and where you struggled. Where you had issues, tweak your practice for the next day. After a week or two, if one strategy isn’t working, try a different one.

As you look for additional strategies and ideas, here are the two best books I would recommend:

- Getting Things Done by David Allen. A little dense at times, you don’t need to apply everything Allen suggests to get a lot of value from it. For me, the most useful was his methodology of how to most effective write and manage your to-dos.

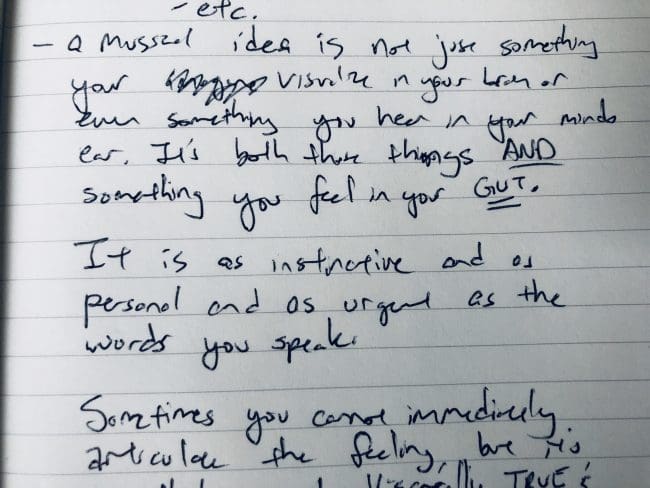

- Staying Composed by Dale Trumbore. Written with composers in mind, it falls into that larger genre of books on the creative process (like Stephen King’s On Writing or Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit). Trumbore offers dozens of practical, actionable suggests that relate directly to working from home and that will make an impact, regardless of whether you are an artist.

As the amount of time we must work from home seems to be getting longer rather than shorter, I wish you the best of luck! As someone who’s been here already, I can say confidently, you can do it!